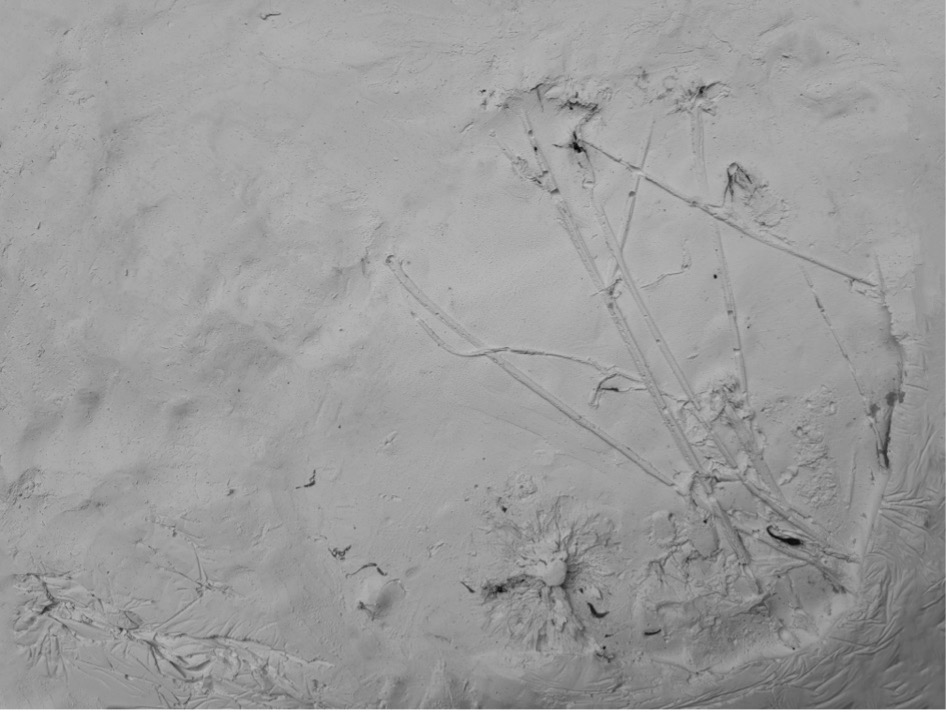

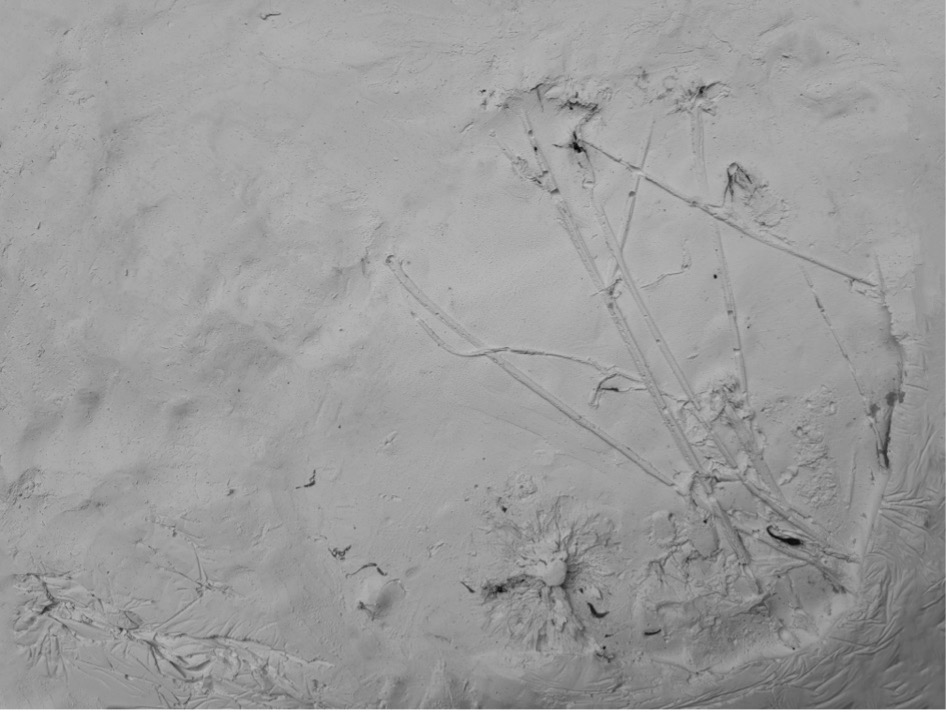

Plate 1 — Dandelion Folly (we reap what we sow)

Our landscape is its own monument: the meaning of its trace only unveils on the underside. It is all history.[1]Édouard Glissant (1981, 21)

In this piece, I follow the geo-temporal meanderings of native grasses (in particular yam daisy-Microseris lanceolate and native millet-Panicum decompositum) through the Australian colonial record and beyond to reveal co-constitutive entanglements which bear witness to a plurality of agri/cultural narratives.

In particular, I draw on the concept of trace as theorised by philosophers Jacques Derrida and Édouard Glissant to explore and produce aesthetic interventions which reveal, shape, coerce and/or support these grasses’ presence and agency—their voices. These interventions (or human-created records) range from the words of Bruce Pascoe (2014) and Thomas Mitchell (1839) through to Jonathan Jones’ exhibition (2019) and my own experience/practice as I research, write and engage with native grasses by making a herbarium and imprinting the collected grasses to produce negative clay moulds and plaster bas-reliefs which capture their material, physical sinuosities and suggest alternative assemblages and affordances of voice and void.

Scattered through geo-temporalities and media, these interventions document—trace—native grasses’ historical experiences and the role(s) awarded to them. Their punctual nature accounts/allows for ruptures, disruptions and (dis)continuities: each intervention carries its own rhythms of the collision between past and future in its midst. This fragmentary state also supports the fluid positioning of voices—the crafting of a textual space where poetics become a tool of decoloniality.[2] Such a juxtaposition of perspectives and representational practices aim to generate intertwining accounts of vegetal being-in-the-world. More precisely, it aims to provide new insights into how native grasses have shaped and been shaped by colonial and decolonial practices—to illuminate their sinuous trajectories with(in) the fabric of the land and provide new perspectives on what constitute agri/cultural practices in Australia.

Philosopher Paul Ricœur explains that “if we want to be guided by the trace, we need to be capable of this withdrawal, of this abnegation, which means that our own concerns fade before the trace of the other” (1985, 182). Creating bas-reliefs requires a physical, material engagement with grasses. I collect, I dry, I arrange and rearrange, I make moulds, I pour plaster, and finally, once it has cured, I reveal (herbaceous traces have appeared and disappeared). There is no space for my own concerns in this process. Herbaceous traces “weave […], in the shadow of a labyrinth covered with mirrors, a tenuous but indispensable guiding thread” (Derrida 2006, 236 n.7). Their vitality directs me and shapes each creative sequence as they imprint their own rhythms upon paper, clay and plaster—upon malleable surfaces.

Through these successive imprints, I endlessly perform and reperform my engagement with grasses. In particular, my textual power of agency recedes in the face of herbaceous traces. They inflect the text’s rhetorical fabric—they dictate its textures: I “only ever follow traces with the finger of the words” (Glissant 1969, 245, original emphasis). Herbaceous traces’ spontaneous impulses propose the placement of words and paragraphs on the page. Like seeds dispersed by winds, like roots spreading far and wide underground, these placements follow unpredictable patterns. Elements interplay with their routes. They respond to humidity, rain and theory; to rock, soil type and word limit. Movements are encouraged or hindered. Seemingly unrelated elements are brought together (encounters happen). Feeble and friable ecomimetic representations metonymically link traces and words. Similarly to Glissant, “I abuse blissful parentheses: (this is how I breathe)” (50). My breath connects me with my environment. Each breath I take revives the traces of the seeds I sent floating in the wind. I imagine them as they germinate in the earth—under the argument and in the curing plaster. We breathe together. This redoubles meanings, reflecting the deeply transformative relationships of vegetal and human worlds—of trace and text (both literary and visual). By teasing a symbiosis between traces and words/artworks, I thus engage in proliferating, redundant processes of meaning-making which are reciprocal and never final. How could they be? Herbaceous traces are indissociable from the notion of fragments—they embody the fragmentary nature of a colonial/colonialised environment: they circle without giving; suggest without revealing. They opacify.[3] By preserving gaps, fractures (silences) in the text, I attempt to signify the ubiquitous presence of herbaceous traces—to weave it within my piece’s very fabric—making this presence non-dissociable, at any given point, from the discussion. Such a design partially answers the ethical challenge of “(re)presenting the stories of others” (Ballengee-Morris et al. 2010, 60), and feminist scholar Patti Lather’s query: “how can writing the other not be an act of continuing colonisation?” (2007, 13).

In following and mimicking the converging and diverging lines of herbaceous traces, I think of Derrida who writes:

to speak of it [the trace] but also to understand that it can, itself, speak and speak of itself, leave traces or legacies beyond the living present of its life, ask (itself) questions regarding its own subject, in short, also address itself to the other. (2006, 235–236 n.7)

Herbaceous traces are not passive: they are participative entities in the process of creating and recording history. However ventriloquially, their voices shine in the text. While remaining subjugated to (contingent upon) my voice, their voices’ presence nonetheless denotes an attempt to question (at the very least) and shift (however partially) the usual anthropocentricity of the academic position (Rose 2009). It also bears witness to the fact that vegetal voices can no longer be ignored: worldwide, environmental crises are forcing us to hear these voices, forcing us to realise that our environments have voices. Philosopher Michel Serres writes:

The mute world, the voiceless things once placed as décor surrounding the usual spectacles, all those things that never interested anyone, from now on thrust themselves brutally and without warning into our schemes and manoeuvres. (2003, 3)

Writing (inscribing) herbaceous voices on page, clay and plaster provides a textual space where native grasses, which do not easily accept colonial reduction and domination, reply. I have chosen to follow Serres’ turn of phrase—I insert them “brutally and without warning” within my work. Such interjections account for (translate) vegetal resistance and defiance of my attempts at discursive control. I design these voices by pressing dried grasses into clay, and by compiling (environmental, historical) data and my own subjective, speculative perceptions. The diversity of representational practices reflects herbaceous traces’ ability to shift and mutate; to travel and return. By manipulating and repurposing loaded modes of representations to display herbaceous voices on page and in plaster, I also transcribe movements, and particularly native grasses’ ongoing trespassing of colonial boundaries, their bubbling in interstices, and their constant push back within the colonial rule, within containment. Their voices rub against mine. I believe that this emplaced plurality of voices is necessary for speech—whether oral or written—to exist. As Derrida writes: “[s]orry, but more than one, it is always necessary to be more than one in order to speak, several voices are necessary for that [...]” (1995, 35). Alone, one voice cannot speak; it cannot say anything. Different voices speak in this piece so that it can come to life.

As I write these words, I am reminded of social justice scholars Jarrett Martineau and Eric Ritskes who explain:

the task of decolonial artists, scholars and activists is not simply to offer amendments or edits to the current world, but to display the mutual sacrifice and relationality needed to sabotage colonial systems of thought and power for the purpose of liberatory alternatives. (2014, 2)

This text responds to their injunction: to produce “liberatory alternatives,” it attempts to implement change, and not simply document it. My textual mises en scène are designed to move across and within emplaced bodies to reconfigure relationships: to reimagine alterity so that alternative ethical positions on environmental crises can emerge.

Plate 1 — Dandelion Folly (we reap what we sow)

I “discovered” the complexity of the Indigenous agricultural system when reading writer Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu (2014). The shock came not so much from learning about the vegetal and human worlds’ co-constitutive and co-dependent economies but from realising that, for years, I had been reading most of the texts Pascoe uses as sources—the journals and diaries of explorers and early colonists—and utterly missed their significance.

Yam daisies (Microseris lanceolata) are tuberous grasses with toothed leaves and tufted yellow flowers. Like dandelions, the florets composing the flower eventually give way to pappi which aid seed dispersal (Atlas of Living Australia 2020; Australian National Botanic Gardens 2016). The first sighting of yam daisies recorded in the Atlas of Living Australia occurred on 4th January 1770 near Wagga Wagga (collector: NSWOBS-05078). Yam daisies grow all over south-eastern Australia, including in lutruwita/Tasmania. Their roots are edible and described as a staple food for Aboriginal peoples by explorers and early colonists (Pascoe 2014, 22–25). Records from the period, like the plants themselves at the time, abound: “[t]he soil of these plains looked rich, the grass was good, and herds of cattle browsing at a distance, added pastoral beauty, to that which had been recently a desert” (Mitchell 1839).

I had failed to grasp the meanings and implications of the vegetal traces recorded within the journals and diaries of explorers and early colonists. Like their writers, I had filtered information and disregarded evidence to craft my own narrative. Theirs is a narrative of beginning: the beginning of possession through surveying—they read the land and think they see the glory of their destiny in its textures. Mine speaks about the beginning of the end—I read the premises of environmental destruction in their words and, as a colonial heir, I (unavoidably) mourn the disrupted fabric of the land (Derrida 2006, 67–91, 121). While seemingly different, these narratives actually perform the same task: they subdue and use vegetal traces to establish a chronology and find causal links. Once more, once again, rhetoric overwrites the physical world, quickly, logically. It obscures and flattens vegetal traces. It denies complexity, entanglements, inheritance, and as such, responsibilities. Such attempted erasures lead to iterative trauma.

Everywhere I go, I collect grasses. I attempt to gather traces whose materiality can somehow follow me home. I also recover traces of vegetal being-in-the-world in explorer and surveyor Thomas Mitchell’s journal. These traces deconstruct narratives of beginning and end. They rebuke the appeal of “the myth of pure lineage”—of the primordial trace—which supposedly legitimates claims (Glissant 1989, 141). Instead, they generate spiralling narratives; tales which bite their tails; tales which, rather than disjunctions, highlight the multiple (and opaque) pre-contact economies and post-contact continuities of the vegetal world.

Vegetal textures run deep. Human selection and manipulation favour plants rewarding their carers with the best and most reliable yields—and maybe the most pleasant tastes. The large and juicy roots of yam daisies are described as “nutty,” “grassy” (Verass 2018), “sweet with a flavour of coconut [... or] more like a radish than a potato” (Cribb & Cribb 1975, 151)—it depends on the sources (and the palates). Sophisticated tilling and burning methods aerate and fertilise the soil, allowing for optimum seed germination and root penetration (Pascoe 2014, 25–26). Harvest methods protect the tuber: only a portion of it can be collected; care has to be taken so that its spared portion does not bruise. Penalties apply to humans failing yam daisies (109). Oblique associations with nonhuman entities (such as encouraged through companionship planting) assist humans in ensuring the survival and prosperity of the vegetal world. Every five years, once seeds have been dispersed, once tubers are dormant, then it is time to burn the yam districts (119–120). Slowly, progressively, human tools, structures and techniques shape plants’ ecologies: habits and genomes evolve, develop, change and become finely intertwined with domestication and agriculture (35–37). Templates of production take shape. These agricultural practices (re)shape the fabric of the land. Harvests increase. Consequently, so do human populations. Reciprocity and co-dependence ensue. Native grasses, and yam daisies in particular, become companion species. Humans and plants rely on each other. They grow together. They share the land.

Early colonial texts, sketches, paintings and herbaria record the extent of the connections between plants and humans in pre-colonial Australia. These objects are not anodyne. Recording invites (re)arranging. These texts, sketches, paintings and herbaria coerce and incorporate what they depict into a European mythopoetic framework. As I press grasses between pages so that they dry, I am aware that herbaria play a particularly important role in that process, for “[p]art of controlling the substance of one’s future would lie in controlling its nomenclature” (Glissant 1997, xiv). Classification tables unfold sculpturally on pages. Lineages are born and drawn out of similarities in shapes and thin air. The story and genealogy of yam daisies is reduced to a string of Latin words plastered on paper like a flattened strand of DNA.

kingdom Plantae

phylum Charophyta

class Equisetopsida

subclass Magnoliidae

superorder Asteranae

order Asterales

family Asteraceae

genus Microseris

species Microseris lanceolata

Through this single (but not simple) act of classification, the ontology of yam daisies is duly documented and then promptly erased. Reality is deconstructed as the physicality of their connections with other entities switches location. Traces on land are replaced with traces on paper; descriptive literature covers the coloured grain of the soil. Words are traced over worlds. And ultimately, ecologies become inhospitable. Microseris lanceolata lies helpless on the page. Disconnected. Alone. Silent.

Yet, this native grass is rich in names and voices: Microseris lanceolata is one of them. Aboriginal Nations who have custodianships of the well-drained, moist soil prefer to call it differently. It is pannin in some Tasmanian languages (“The Murnong Story” 2019); it is murrnong in eastern Kulin (Clark 2014); it is ngampa in the Thura-Yura languages (Simpson and Hercus 2004). It depends on where bodies stand. Names encapsulate emplaced relationships: they bear witness to networks of connectivities. When Europeans encountered the cultivated fields, they overwrote this plurality of names with a singular patronym: the native grass became Microseris scapigera. The name was itself overwritten as quickly as it had overwritten others. Originally thought to be connected to a similar-looking grass in New Zealand, yam daisies were eventually found to be a different species and promptly renamed to reflect this more accurate classification (Atlas of Living Australia 2020).

Maybe this process of classification is bound to fail regardless. After all, it is an “enormous task, to make an inventory of reality. We amass facts, we make our comments, but in every written line, in every proposition offered, we have an impression of inadequacy” (Fanon quoted in Glissant 1989, x). All we manage are traces, black on white memories of co-constitutive ontologies. Native grasses are (re)arranged in cross-referenced herbaria: they belong in (are relegated to) dark archives. The traces they deposit in these monuments of Western knowledge are traces of persecution, “whitewashed” memories epitomising the alienation of humans from their environments through sanitising colonisation (105).

The superseding of a Latin nomenclature over a plurality of emplaced names obfuscates co-sustaining relationships. It isolates native grasses, sectioning them from the ground, tearing them from their beds as surely as the blades of livestock’s teeth. It dissociates them from care. Duties and responsibilities, no longer embedded in vocabulary, are disregarded. Monster ploughs replace careful hands and specifically tailored tools. Ripping replaces tilling. Eaten alive, washed in acid, spat back up and down and up and down again, yam daisies travel back and forth through exotic digestive tracks. The drawings which accompany the botanical text prolong this tradition of separation. Poet Juliana Spahr elaborates:

They made drawings of isolated plants against white backgrounds. The drawings are undeniably beautiful. But there is little reference to where the plants grow or what grows near them or what birds rested in them or ate their seeds and fruits or what bees or moths came to spread their pollen or how humans used them or avoided them. (2011, 69)

Symptomatic of the constant (re)establishment of the schism between nature and culture, botanical metonymy fetishises symbols while remaining oblivious to the place of entities within their larger environments, and the repercussions of their presences/absences on said environments. Microseris lanceolata unplaits emplaced relationships, it crosses them out, it denies they ever existed. Such incisive practices perform a constant (re)imposition of the colonial imaginary on the land. Sheep and cattle continue to be written into breeding; native grasses continue to be turned into weeds and museum relics.

Yet, herbaceous traces still speak through the page. Their poetics yells at me in the gaps of this over-detailing nomenclature. I try to reconnect paper and land. I alternate between studying botanical drawings and searching for live plants which resemble yam daisies. There is none. All I identify are other instances of Microseris; invasive species which feed on my hope and lack of knowledge to take over the space. Yet, I still stop the car, right now right here, every time I spot a yellow flower by the side of the road. New voices regularly join my herbarium. I no longer rush in a straight line, in search of beginning and/or end, in a display of “arrowlike nomadism” (Glissant 1997, 12). I retrace my steps. Detours occur. Yam daisies lift their heads when flowering so that pollinators can easily access their nectar. Livestock gorge on it. Their teeth dig deep into the luxuriant green flesh. The milky sap makes them salivate profusely—it is so highly palatable. Yam daisies lift their heads again when their pappi are ready to be disseminated by the wind. In the cold morning, livestock’s warm breath tickles them.

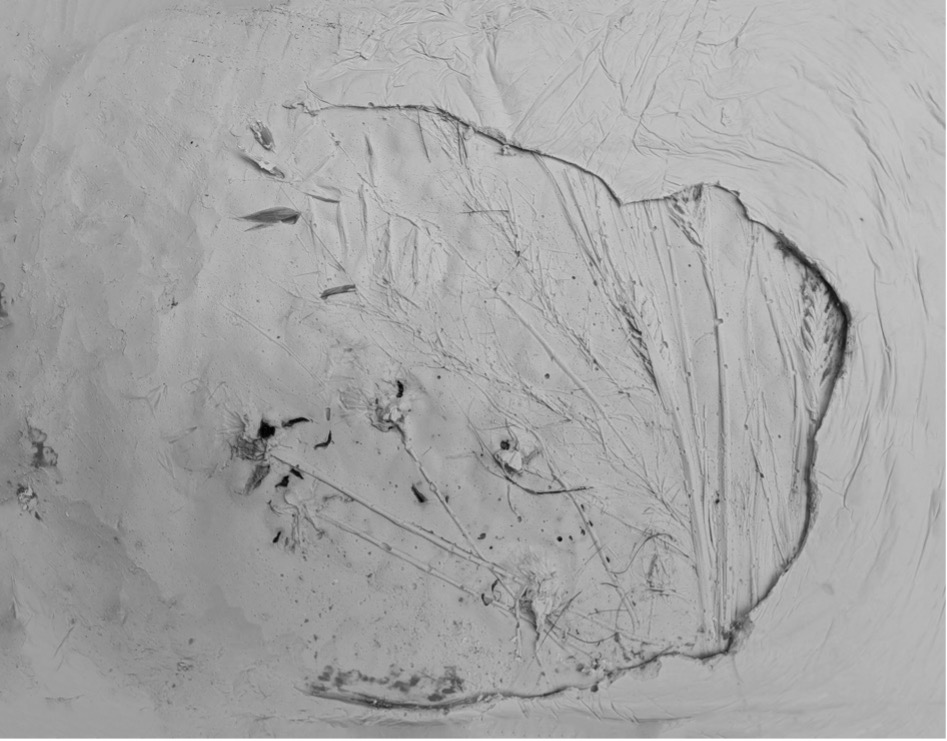

Plate 2 — Dandelion Folly (we reap what we sow)

Unlike kangaroo’s feet, the hooves of introduced sheep and cattle lead to erosion. These hooves spread the European mythopoetic framework from page to land. They physically enshrine the overwriting heralded by botanical metonymy. As herds trample the land, its spongy and rich soils rapidly deteriorate. They are transformed into a hard surface which favours water run-offs and damaging floods (Pascoe 2014, 25–26, 43). Over 100 million heads of livestock now populate Australia. It is a stampede. The soil is compressed. Grasses recede. Boots, hooves and bulldozers lay the foundations of a new ecology. From plains to stomachs, compacted seeds asphyxiate. Fifty-two plants are listed as extinct under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Traces are signs of loss. They hide in the soil, under the broken fabric of the land.

Native millet (Panicum decompositum) is a perennial grass which grows in dense tufts of up to 1.5 metres tall. Like wheat, its glabrous and tough leaves taper to a fine point, and its seeds are nested in open panicles which break off and blow away when mature. The first sighting of native millet recorded in the Atlas of Living Australia occurs on 1st January 1770 somewhere in NSW (collectors J. Banks and DC. Solander). Native millet grows everywhere in Australia, except in lutruwita/Tasmania (Atlas of Living Australia 2020; South Australian Seed Conservation Centre 2018). Its seeds are edible. Ground, they make damper, a staple food for Aboriginal peoples according to explorers’ and early colonists’ records.

Fire-stick farming is precise.[4] Colonial records unwillingly indicate that each grass, each plant, each portion of the land, has its own rhythm of fire (Pascoe 2014, 119–20). This multitude of regimens answers to the ecology of each grass, each plant, each portion of the land. It optimises interactions and ensures enhanced yields (122–123). Relationships and entities flourish. I arrange and rearrange the dried grasses on the flattened clay. I handle their fragile pappi carefully: care means that the seeds won’t detach.[5] I then use all my fingers to slowly press them into the clay. I think of how I am reinscribing them in soil after severing them from their soil of origin. Their new soil is uniform—it does not take their particular histories into consideration. Under my fingers, each grass is made to carve new relationships: they push against the clay and each other. As I work, I conceptualise their resistance or concession as the expression of their agency. Native millet flowers in autumn and summer. Its spikelets turn orange, red and purple like a sunset. Its vibrant green leaves dry the colour of wheat. I think of explorer and surveyor Sir Thomas Mitchell, who recorded in his journal (1839) that he “saw a numerous family of kangaroos this day, but although the dogs were let loose, such was the length of the grass, that they could not see the game.”

Colonisation interrupted Indigenous agricultural rhythms by imposing imported rhythms whose intransigent and tyrannical character disrupted widespread patterns of alliance and coordination. Coercive and demeaning relationships replaced processes of cooperation and collaboration. Textures were rapidly inflected: “what had been productive agricultural land became scrub within a decade” (Pascoe 2014, 118). Understorey overtook fertile plains.

kingdom Plantae

phylum Charophyta

class Equisetopsida

subclass Magnoliidae

superorder Lilianae

order Poales

family Poaceae

genus Panicum

species Panicum decompositum

Philosopher Henri Lefebvre argues that “[w]hen relations of power overcome relations of alliance, when rhythms ‘of the other’ make rhythms ‘of the self’ impossible, then total crisis breaks out, with the deregulation of all compromises, arrhythmia” (2004, 99–100). Subjected to great tensions, a large portion of native grasses’ habitat is deformed beyond instantaneous bodily recognition and ontological comfort: features are altered, disfigured, chopped and desecrated. Herbaceous traces retreat as a result of this arrhythmia. On the hard surface, they appear shaped into submission, into oblivion. Wind, salt and dust beat plains whose soil is no longer protected, anchored by roots.

An iconography of the land binding native grasses with humans is altered beyond instantaneous recognition. The soil is no longer where the traces of their relationships are etched. Instead, it becomes an “impressionable surface” (Carter 2010, 37–38). Ploughs march. They scarify the body of the land. Affordance hides. Spatial historian Paul Carter writes: “[European a]griculture is a culture entire, a mode of dreaming places into being. The clearing integral to its practices is also the ‘clearing’ of Western knowledge in which the light of reason is cultivated” (34). Panicum decompositum is further divided into seven varieties and three forms. Rhythmic fragmentation grows.

By rupturing co-evolving symbiotic agencies and severing bodily connectivities, European agriculture impedes the fluid dynamics of “meshwork,” that is, the concatenation of rhythms which interpenetrate and configure each other (Ingold 2011, 71). Osmotic-like relationships between human and native grasses dissolve. Colonisation means that the land is occupied, rather than inhabited. Traces of embedded being-in-the-world are challenged by traces of a theatrical occupation of space. Panicum decompositum is highly prized as pasture for livestock. It “persists” best on clay soil under rotational grazing. If overgrazed, it becomes infinitely tall and less palatable (“Native Millet” 2020). It protects itself.

As I hike on the land, I feel the rhythmically unsound contours of landscape. Concreted carparks and signage delineate where I am to walk. Watch towers and fire truck are omnipresent in the background—always ready to let their sirens tear through the land in attempts to extinguish the ramifications of colonisation. This colonial racket long reverberates in the apocalyptic skies. All else falls silent. Philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy discusses the consequences of such an interruption:

When a voice or music is suddenly interrupted, one hears just at that instant something else, a mixture of various silences and noises that had been covered over by the sound, but in this something else one hears again the voice or the music that has become in a way the voice or the music of its own interruption: a kind of echo, but one that does not repeat that of which it is the reverberation. (1991, 62)

Masked by the sirens of colonisation, herbaceous voices seem inaudible. And yet, it is through this silencing—through this interruption—that they precisely start speaking the loudest. For their voices are no longer solely rooted in place, connected to physical entities. Rather, this silencing produces endlessly morphing echoes—traces—with a life of their own. As Carter writes, “[t]his is the psychological depth of echoes: not to talk about the past but to resound it, easily, naturally” (1992, 19). Pushed underground by bulldozers, scattered by human hands across colonial paintings and museums, relegated to the periphery by pesticides and fertilising superphosphates, traces of native grasses rebel like weeds: they start to multiply, to exist “beyond presence and absence” (Derrida 2006, 238 n. 12).

I pull the dried grasses out of the clay and all I see is the void left by their removal—curved and straight lines, dots of various shapes and sizes, all imprinted in the clay; hollow outlines where matter used to be. These traces are the haunting presence of an absence. Tenuous, fragile, always on the verge of dissolution, they carry the memory of their own disappearance. Anachronistic as much as prophetic, they contain that “[w]hich, moreover, never fails to happen also, but it happens only in the trace of what would happen otherwise and thus also happens, like a specter, in that which does not happen” (34, original emphasis). Herbaceous traces are alive. Following them results in being followed by them, in being “persecuted perhaps by the very chase” (10). As I pull up the weeds in my garden, I notice that their roots now run under the concrete slabs, allowing them to sprout in the driveway. Pavers move. The chase induces a notion of ineluctability: there is no escape. Herbaceous traces surround me, obsess me—I constantly attempt to grasp them; I fail over and over again. Their biology, their ecology, their distribution continue to blur. They flourish in every interstice—on the sides of highways, in unkempt nature strips, in the background of homemade documentaries and amateur collages, in the darkest corners of our parks and gardens. They scatter their invasive traces over everything that remains. As Derrida explains: “[a]nd one must reckon with them. One cannot not have to, one must not not be able to reckon with them, which are more than one: the more than one/no more one” (xx, original emphasis).

The instantaneous, fragmentary, disparate (heterogenous) plurality of traces implies an always-disjoining-and-colliding motion—an “irreducible distortion” which forces those who interact with them to undergo a “ceaseless recasting” (Blanchot quoted in Derrida 2006, 43). Herbaceous traces oblige me to endlessly reassess and redefine the terms of my relationships with them—to indefinitely confront the complex, traumatic legacies of destruction which drove vegetal ontologies underground; the complex, traumatic legacies which continue to deny native grasses their agency and persona. Following herbaceous traces reveals debts: it reveals the repercussions of colonisation on the Australian biotope; it highlights the damage we have caused. Traces constantly remind me of my duty to bear witness—of my duty to remember, follow and imagine, for as Derrida states, “[t]o be haunted by a ghost is to remember what one has never lived in the present, to remember what, in essence, has never had the form of presence” (1983). And so I keep looking for herbaceous traces. I handle the clay mould with great precautious: one misplaced finger could easily smudge and erase what I am trying to find.

Daily, pockets of remnant vegetation in highly urbanised areas remind me of how I am failing native grasses. Chiselled apices point fingers. Each pocket carries “life beyond present life or its actual being-there, its empirical or ontological actuality: not toward death but toward a living-on [sur-vie], namely, a trace of which life and death would themselves be but traces and traces of traces” (Derrida 2006, xx, original emphasis). Each pocket carries the memory of a plain. Baroque excess fills these interstitial spaces. They indefinitely grow and multiply. They resist. They proliferate. They signify everything and/or nothing—the fertile plain and the barren desert; sustainable land management practices and intensive farming methods; the coming and going of renters, owners, lawnmowers and hoes. They are constantly renewed, never finite. The inherent plurality of herbaceous traces resides and thrives in these pockets. The trace is redundance (it is repetition). This disrupts both logic and linearity—it disrupts certainty. As Carter writes, “[i]t is by keeping open the possibility of another meaning, of another position emerging, that ambiguity assumes its responsibility” (1992, 17). The trace is tension (it is both what is occulted and what is revealed). I watch lines and dots disappear as I pour the plater over the mould. The trace is a tension born from the unfinished and ambiguous nature of any unveiling process. Baroque excess never occupies (colonises) space but lives (breathes in and with) it. It fosters and protects a proliferation of legacies and inheritances. When I softly shake the mould to be sure that the plaster has filled every possible space, some air bubbles surface. It makes me feel that the traces left by the dried grasses are breathing.

I patiently wait for the plaster to set and cure. The flamboyance of the pockets’ herbaceous traces demonstrates that totality can only be imagined (grasped) and never encompassed (captured). These pockets thus embody the power of the irreversibly, irremediably opaque trace as a “nonprojectile imaginary construct” (Glissant 1997, 35). There, herbaceous traces speak of and open an infinite plurality of potentialities for native grasses. They forge tales which both echo and transcend physical absence or presence. They compose (their own) histories and futures through constant retelling (reformulation). Their agency is communal, multiple—mobile. It is unpredictable. Placed in contact, they (inter)react: they transform, merge, collide, confront, connect or repulse each other. They blur and undermine boundaries. To paraphrase Derrida, they work (2006, 9). They are in-becoming. They simultaneously assemble (are inspired by all grasses) and singularise (preserve the emplaced unicity—the integrity—of each individual strand of grass). By doing so, they ensure that native grasses cannot be transformed into projects. This is how they survive—this is how they thrive. This is how they overcome the controlling dissection of the botanical metonymy. It reaffirms their capacity (right) to disappear in the ground (to hide and protect), to reappear at the turn of a path, to proliferate in plains, in crevasses, on top of mountains, on the side of roads and railways, on the fringe of industrial estates, in alpine fields, woodlands, moist depressions, stream banks, on the margins of salt lakes and samphire flats, on fenced-off margins where no hoof, pesticide or fertiliser can reach.

Herbaceous traces do not negate contradictions. Rather, they hint, they allude, they trace the many paths, marks, tracks of colonialism’s ramifications (they draw these words while I am still waiting for the plaster to fully dry). Their imagined totality contains both sacrificed autochthonous biotic authenticity and imposed biological hybridisation. They opacify to preserve and express the mass of the unsaid (the impossible to say), of the inhibited, of the repressed. They are the primordial cry: what stands silent in-between the words, what is left unspoken after a comma; what has several meanings, what is multilingual; what depends on contexts. They suggest an in-between space of creative frictions, attractions and repulsions which materialises a disjointedness through which I can be alert to what is not being spoken out loud. There lies the possibility of hearing—that is, of (re)imagining—silenced (silent) voices.

Once the plaster is finally cured, I slowly peel off the clay mould, layer by layer. Captured in reliefs once more, the physical presence of the trace is revealed. It becomes palpable: void has become voice. As I write, I realise that these words sit uneasily with the opacifying (po)ethics that I defend. My textual explorations of herbaceous traces imply that I attempt to represent the unrepresentable: to signify the (ongoing) attempted ecocide promoted and carried out by a large portion of the settler imaginary to which I belong. As philosopher James Hatley writes:

the very attempt to memorialise the annihilated by giving them a body beyond their own within […] this essay would be a betrayal. Such a gesture would repress the very significance of the other’s vulnerability by acting as if the other’s nudity were somehow capable of even the most cursory translation, the most tentative appropriation, as if one could feel the pain of the other for her or him. (2000, 246)

I agree that vulnerability is precisely what must be protected: its incommensurability composes traces. I do not pretend to translate this incommensurability. I only speak of and through my own experience of inheriting both cries and silences, presence and absence, presence-as-absence and absence-as-presence. I centre my words on my subjective engagement with herbaceous traces as they manifest as charred fragments or incandescent jungles. If this piece translates vulnerability, it is my own: treading on Australian land is never an easy nor anodyne act for a non-Indigenous person. I only speak from where I stand—I type these words on unceded Kaurna Yarta. I am acutely aware of the duties (of the ambiguities) of my position as a non-Indigenous researcher concerned with herbaceous traces. This is what my in-text performance (whether written on a page or in clay and plaster) highlights. Being performative means taking risks: it stresses my emplacement, along with the limits and inherent flaws of my practice, for there is no such thing as a finished or perfect performance (Dening 2009). But risk-taking is necessary. I remember Martineau and Ritskes’ injunction (2014, 2): how else could “liberatory alternatives” be produced? Being performative represents a way to leave room for the unsaid and the unsayable—for the “Other.” It implies that my voice, while bearing—and even exceeding—meaning, assuredly remains “recalcitrant” to its production: it is “what does not contribute to making sense” (Dolar 2006, 14–15).

Only through readers and viewers engaging with herbaceous traces on their own terms—by themselves—is sense to be made. But make no mistake: this is not an exercise in abstraction. Native grasses fiercely resist abstract manipulations—they have physical bodies; they have plans. I once hung yam daisies’ flower buds upside down in a dark space in an attempt to find an alternative method of preservation. The flowers opened and then turned into pappi. They dispersed their seeds everywhere. Scattered alongside highways, buried in dark museums, dispersed in artworks and books, their traces hint at something much more concrete: relationships. More precisely, their materiality offers (is) and promotes a dynamic relational model characterised by reciprocity. Despite the distortions inflicting by colonialism upon our connections to biotopes, they show us how (they invite us), through aesthetic and imaginative processes, to reinvent our relationships with others not by appropriation or reduction (for how could what can never fully be encompassed be ever possessed?), but through resounding dialogues across disparate spatiotemporalities. Dialectical partners are key to any unveiling, (un)making process.

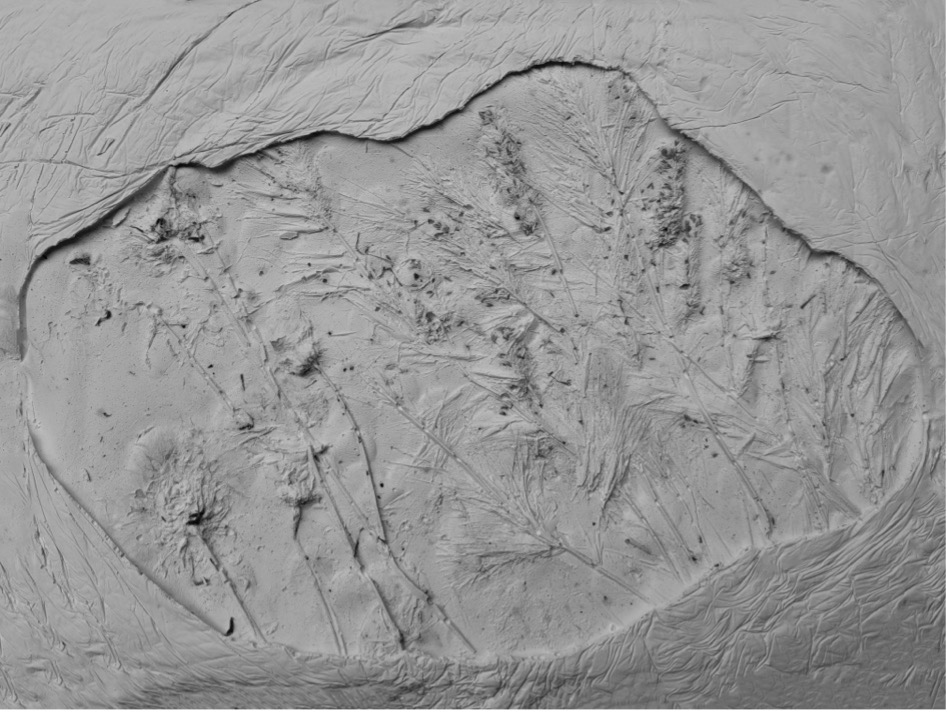

Plate 3 — Dandelion Folly (we reap what we sow)

Fires return. Uncontrollable, wild, they tear through the land. The army is deployed—we are at war. I watch the news and think of investigative journalist Jess Hill who explains: “the original Greek word for apocalypse—apokalypsis—does not mean ‘end times’. It means ‘to unveil’. This is the apocalypse we are living through: a process of unveiling and revealing” (2020). Seeds and tubers dance in flames. They burst and disperse. “They trace the void, through overly measured explosions” (Glissant 1989, 238). Grasses joyously erupt through the soil in the aftermath. They are reminded of the fire-stick farming methods which had become part of their ecology. Old horticultural rhythms are coming back to life. Some of the land’s textures are regenerating. But how could I forget that these flames mostly destroy? Too hot, too high, too widespread, their burning tongues articulate the grief of plants into being. Our environments are calling. They are sending us costly reminders of our neglect, of our technological detachment which led us to believe that we had everything under control—as if we could.

The devastation of Ash Wednesday in 1983 was followed by a “phenomenal” flowering of native grasses, and especially of tuberous perennials (Niewojt quoted in Pascoe 2014, 120). So was the 2019 Cudlee Creek bushfire. The next spring, I hike in the nearby hills. Lush vegetation and skeletons of trees now cover the areas which burnt. The vibrant green of tall native grasses and thousands of saplings attracts the eye, an oasis of softness in the otherwise harsh, bronzed landscape declined in shades of yellows. I create more and more plates to add to the Dandelion Folly (we reap what we sow) series; I add more and more grasses to each plate of the series; this growing number of plates and the increasing density of the traces they contain are translated into more and more words on the page—I imagine a totality (never totalising), which is driven (and stretched) by appositional richness rather than by reducing similitudes. This totality is fragile. It is unstable, partial, fragmentary, incomplete. It is forever expanding. It is boundless, open (to interpretation, to rewriting, to disintegration); open to become another totality, already. It is a totality-in-becoming. The “additive and accretive” nature of my approach is part of a reflective, reparative impulse (Sedgwick 2003, 149).

The performance of such a reparative impulse is ambiguous: it is not about repairing stricto sensu—it is about tolerating ambivalence (126). It is about positioning damage and care on the same plane, about holding them together on paper, clay and plaster in the same way that they comingle and co-exist in herbaceous traces. Such a performance attempts to signify the irreversible (or at least, not yet reversed) damage inflicted upon grasses, while also acknowledging and/or suggesting (re)constructive practices and alternatives. This ambiguity might be fed by the trace itself: it is both what is gone and what remains (what will come); it is void and voice. The process of creation of the artworks materialises this, where the meaning of damage, while always present, also constantly morphs.

Beyond flames, grasses are talking to us. Their discourse is fragmented, disjointed: it no longer comes from a position of co-dependence. Their thriving in the aftermath of fires that most humans desperately try to avoid and quell highlights a profound shift (a palpable rupture) in the relationships between vegetal and human worlds. It is a rupture in practice, a rupture in epistemology. And yet, what the fires and the grasses’ reactions to them prove is that this rupture is in no way a severance. Flames, seeds and tubers remain involved in an intrinsic and fascinating pas-de-deux. Fires feed on plants and plants regenerate and spread through fires. They take their steps together on the stage of the land. The rupture is the sign of a fluid and immanent remaking—traces spontaneously combust to fuel constantly shifting new potentialities: “[a]nd not only the living is not afraid to stop, but it seems that the rupture is one of the steps of its advance. The rupture of the living is often the chance that is in it and that builds it, unmaking it for an elsewhere or an otherwise” (Glissant 2017a). The confluence and repulsion of historical forces that this rupture embodies sketches a connivence: paths (possible futures) are drawn in ashes. They speak of the need to shift unsustainable practices. They hint at ways in which sustainable practices could be rekindled; ways in which they could be reawakened afresh.

And some have been listening (some had never stopped). Old, revived and new practices have been burgeoning, as illustrated by artist and curator Jonathan Jones’s exhibition Bunha-bunhanga (2019) which retraces the layers of meanings humans have attached to native grasses. At the Santos Museum of Economic Botany, Jones brings together excerpts from Mitchell’s journal, pages from the State’s herbarium collections, grindstones, soundscapes and sketches drawn over old newspapers. This juxtaposition of colonial and Aboriginal imaginings/objects continues at the Art Gallery of South Australia where, within the same space, Jones displays colonial paintings depicting landscapes bearing the undeniable marks of Aboriginal land management practices alongside some of the tools used to shape these landscapes, bouquets of dried native grasses and jars of their seeds/grains.

Art/fiction writer Prudence Gibson and evolutionary ecologist Monica Gagliano write that “[a]rt is more than a representation, more than a means to uplift (although it can do that too). When art is good, it instils a commemorating force” (2017, 140). Jones’ work most certainly acts this way. Inspired by Pascoe’s research, it offers a striking visual representation of his findings: traces intertwine with traces of traces, to paraphrase Derrida. The exhibition also demonstrates that colonial art “instils a commemorating force” too: beyond its intent, it safekeeps the very environmental voices and relationships that it is also attempting to erase. Its failure then, is not a failure of perception, but a failure of interpretation. It is the product of a culture which is not trained to read (to learn), but only to possess. As Glissant states: “[a]t bottom, the trace is truly trace, that is to say a figure of the collective unconscious” (1957, 29).

Like Pascoe, Jones does not pretend to be rewriting history: “the history was written by other people” (Pascoe quoted in Marsh 2019). Instead, by exploring Aboriginal relationships with native grasses through early colonial artefacts, Jones generates forced juxtapositions which recontextualise and reframe (recalibrate) History. He provides a space where the overwriting of a sophisticated agricultural system by ill-adapted practices imported from Europe feels palpable, obvious. Jones explains that “this process of unraveling is something people who have been left on the periphery can do best, un-packing and re-packing, within new cultural models, which often takes the material we know and shifts it into new light so it can be seen afresh” (Baillie 2016). Such a discerning analysis reminds me of Derrida, who ponders if “the end of history is but the end of a certain concept of history” (2006, 17, original emphasis). After all, history is nothing more (and nothing less) than the science of traces (Ricœur 2003).

Herbaceous traces act as sites of memory. They are testimonies; they carry tracks and histories in their midst—my role is to follow and listen. And as such, beyond commemoration, Jones’ juxtapositions produce a spatial grammar which requires constant (re)interpretation. Shifting associations arise as painted, recorded, sketched and dried traces interact. They come together; assemble, connect, disconnect and reconnect; morph and move, forever deconstructing the linear pattern of the colonial order to preserve their agency and multiple layers of being-in-the-world, never occulting the complexity of both their ontologies and the repercussions of the colonial encounter upon them. Seeds disperse in the wind. Meanings keep proliferating—boundless, imagined, future. Bunha-bunhanga means abundance.

These juxtapositions generate an accumulation of meanings. Their imagined totality is not the sum of all parts but represents their relation to come and leaves the conclusion unresolved (Glissant 1969, 90). The unforeseeable nature of traces’ imaginary fusion/friction suggests and/or fosters the development of a flexible and polymorphic in-between space. In this space, times and geographies tangle. Chronologies, these “passive heirs to the past” (Glissant 2000, 8), se choquent et s’entrechoquent like creolising languages. They collapse. This leads to the articulation of an autochthonous longue durée defined outside of cultural notions of time. It activates interstices for what is not (yet) known, what can (no longer) be told, what is to happen. This is not solely happening within institutional walls. It is also taking shape in the open, underground, in seeds and tubers. Herbaceous traces work (as Derrida argues)—on soils and in minds.

Agricultural projects involving herbaceous traces are flourishing all over Australia. The shift in human practices that they require remains limited: only plants suitable for human consumption, plants which appear to be at the service of humans, are concerned. Yet, for this service to be provided, such a shift nonetheless requires a redefinition of the terms of the relationship between human and these specific plants. Native grasses do not require irrigation, pesticides or fertilisers (Pascoe 2014, 37, 52). Instead, they request of humans to respect their environments. Productivity does not come through degradation but through enhancements which rest on reciprocal networks of care. As environmental biologist/plant ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer explains, all things are interconnected and “[a]ll flourishing is mutual” (2013, 15). The revival of these grasses’ cultivation in Australia is articulated as a potential solution to the multiple environmental crises assaulting the land (Pascoe 2014, 146). New narratives emerge and frame native grasses as extremely nutritious saviours.

The rebirth-survival of agricultural practices which rely on reciprocity points towards a (re)connection with the soil—demeaning global pressures gives way to multitudes of local energies. Haunted by herbaceous traces, some humans revive economies of co-dependence in mutated forms. An “alterbiopolitics” (“alternative paths in the politics of living with care in more-than-human worlds”) is in its infancy (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017, 130). It slowly reconstructs moments of exchanges where tubers grow larger and seeds more numerous in response to human care. Recipes (re)surface—traces of knowledge from time immemorable interact with creations influenced by international cuisines. As Pascoe explains, “[t]elling a historical story through food is a gentler way than talking about massacres. We need to talk about massacres, but if we want real improvement, perhaps we need a gentler conversation” (2021, 131). This favouring of reparative discourses over privileging the exposure of wrongs is contentious (Sedgwick 2003, 126), and by Pascoe’s own admission, not ideal. However, it might represent a necessary step in the process of crafting spaces of exchanges from which an alterbiopolitics can grow. Pascoe’s statement makes me think of the words of visual artist Judy Watson. I keep them in mind as I press grasses in between pages:

Art as a vehicle for intervention and social change can be many things, it can be soft, hard, in-your-face confrontational, or subtle and discreet. I try and choose the latter approach for much of my work, a seductive beautiful exterior with a strong message like a deadly poison dart that insinuates itself into the consciousness of the viewer without them being aware of the package until it implodes and leads its content. (Watson and Martin-Chew 2009, 226)

Reparative practices which orient or aestheticise histories are not about avoiding unpleasant truths; they are about getting their human audience to engage. And the rest will come later. Once engagement has occurred, then listening and awareness become possible.

Grasses’ cultivation and their culinary uses provide that pathway. Traces travel through bodies—they gain new physicalities. I remember making dandelion salad as a kid in France. I remember how much I loved collecting the leaves in the fields and how much I disliked eating them because of their bitterness and chewiness. Now I crave their taste and texture. I hunt for their trace in rocket and watercress leaves. Intimate gestures of food cultivation and preparation are conduits for renewed relationships. As Pascoe explains, seeds and tubers are “more than a commodity; [they are] a civilising glue” (2014, 137).

Following herbaceous traces apposes colonial and decolonial imaginaries. This illustrates what Glissant calls an “aesthetics of the earth” (1997, 150). Embodied in traces, this aesthetics is born from entanglements: cultures and biotopes endlessly collide and collapse in its midst. Their traces constantly emerge and recede. The costs of these encounters on and through the soil is at times obscured, but never obfuscated. For there is a (slight) difference between the physicality and poetics of the soil (Glissant 1981, 262). One cannot be reduced to the other. The soil swallows traces—and its poetics seeks to retain, translate, elucidate and unveil these traces. As such, an aesthetics of the earth preserves and/or reconstructs the opacity of a soil ploughed by colonialism, of a soil intentionally flattened, deliberately rendered uniform; of a soil wished without traces—without pasts. Chiaroscuros and veinings (re)appear: herbaceous traces only unveil on the underside.

[…] sap wallaby grass kangaroo grass like a field of wheat three feet tall wild sorghum blown grass native flax seeds hovea pods cumbungi common reed water ribbons 200 tubers per plant tall and tuber spike rush slender bitter cress leaves and stems marsh club rush tubers roasted pounded into cakes nardoo sporocarps soaked ground […] (Crisp 2019, 21, original emphasis)

In (re)staging the critical entanglements of human and herbaceous traces, Louise Crisp’s poem—like Jones’ exhibition, like Pascoe’s text—exposes and delves into the fracture lines of the colonial narrative. My approach is similar—it is phytographia: “the encounter between the plants’ inscription in the world and the traces of that imprint left in literary works, mediated by the artistic perspective of the author” (Vieira 2015). Phytographia intimately intertwines plants and humans’ sensibilities and ontologies—it patches their forms together like a collage. It embodies the promise of a world constructed on their co-dependence: one can no longer thrive without the other. It demonstrates the futility (irrelevance) of attempting to impose a supposedly logical progression on native grasses—they have their own agency, through wind and soil, through chemical emissions and ecotransmissions. It demonstrates the fragility (impermanence) of our hybridised biotopes. It highlights the need to live in (celebrate) their ephemeral forms. Because, as Glissant explains, “[t]he suffering of […entities] cannot be spoken; only their hope, their presence” (1969, 13).

Such works reassert that following traces corresponds to going through an infinite process of unveiling (Glissant 1969, 177–180). There is no end; there is no truth— only a “way of existing in the world” which represents “a lasting suspension between the impossible-to-know-of a beginning and the impossible-to-foresee of end” (Glissant 2017b). Such a process is vertigo—past endless collapses into presents, into futures. It does not seek to elucidate or resolve the destructive outcomes of colonisation; it does not “presuppose an immediate or harmonious end to domination” (Glissant 1996, 106). Vegetal and human worlds remain a long way from prospering through tight collaborations. Instead, such a process highlights the need to relate and co-evolve in infinite spiralling, cyclical mosaics. It highlights the need to disallow and recast representational models (patterns) which reproduce and sustain the destructive subjugation of the vegetal world at play in any instance of domination. As Serres injuncts: “[o]ur voice smothered the world’s. We must hear its voice. Let us open our ears” (2014, 42).

I grew up surrounded by wildflowers. Daffodils, dandelions and buttercups took turn in colouring my world yellow in spring. Now a city-dweller, I witness how biomimicry fills medical and architectural spaces. The vegetal world is part of our constitutive mythology. It punctuates and permeates our identities and practices (actions). It defines who we are. Its sinuous traces contain it all: what has already happened, what is in the making and what will happen. Following them reveals this world’s shaping force—or, to extrapolate on Glissant’s concept of “geomorphism” (2006, 176–177), it reveals its “chloromorphism” (a vegetal poetics integrates and transcends humanity).

Our legacies of fire encircle us. Subterranean flames spread through roots in rich soils. The apocalypse has arrived. Native grasses endlessly unveil and reveal themselves within and beyond human records. They leave traces for us to follow; traces which hint at other ways to perceive and relate to them. Through roots, tubers and seeds, their intricate patterns of being-in-the-world play a mediatory role: they enable humans to teach alterbiopolitics, in the sense of Glissant who writes: “[t]each, that is to say: learn with” (1969, 245).

[1] All translations from French are mine.

[2] My understanding of decoloniality is nested within the oeuvre of Glissant, who articulates it as the necessary discursive deconstruction and fragmentation of the uniformising pressures imposed by colonialism (and later, globalisation). It requires to embrace the unity-diversity of knowledges and modes of knowledge production encapsulated in languages, where words sustain sensibilities and imaginaries which are being constantly reinvented through repetitions, reiterations and accumulations. As such, decolonial thought acts as a barrier against any kind of anthropo-andro-Eurocentrism.

[3] I envision opacity after Glissant, as a mechanism against appropriation (1990, 67–68). There is a loveable opacity in the term “trace” itself, rich of so many definitions, deliciously unbounded and constantly reshaping. Traces are tracks, paths, marks, signs, imprints. Interestingly, Derrida deliberately refuses to use a single term to refer to traces: among others, specter and différance carry similar meanings (2016, xxxiv).

[4] See Pascoe 2014, 48–49 for further details/references on fire-stick farming.

[5] As I proceed, I also recall environmental biologist/plant ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer explaining how, in Potawatomi culture, sweetgrass is braided “to show loving care for [the earth’s] well-being” (2013, 203).

Atlas of Living Australia. 2020. https://bie.ala.org.au

Australian Government. 2000. Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C2004A00485

Australian National Botanic Gardens. 2016. Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, Canberra. Last modified January 18, 2016. https://www.anbg.gov.au

Baillie, Tamara. 2016. “An Interview With Jonathan Jones.” fine print 9. Accessed November 2, 2020. http://www.fineprintmagazine.com/jones-baillie .

Ballengee-Morris, Christine, James Sanders, Debbie Smith-Shank, and Kryssi Staikidis. 2010. “Decolonising Development Through Indigenous Artist-Led Inquiry.” Journal of Social Theory in Art Education 30: 60–82.

Carter, Paul. 2010. Ground Truthing: Explorations in a Creative Region. Perth: University of Western Australia Press.

———. 1992. The Sound in Between: Voice, Space, Performance. Kensington: New South Wales University Press; Strawberry Hills: New Endeavour Press.

Clark, Ian D. 2014. “Dissonance surrounding the Aboriginal Origin of a Selection of Placenames in Victoria, Australia: Lessons in lexical ambiguity.” In Indigenous and Minority Placenames: Australian and International Perspectives, edited by Ian D. Clark, Luise Hercus, and Laura Kostanski, 251–271. Canberra. ANU Press. http://doi.org/10.22459/IMP.04.2014

Cribb, Alan Bridson, and Joan Winifried Cribb. 1975. Wild Food in Australia. Sydney: Williams Collins.

Crisp, Louise. 2019. Yuiquimbiang. Carlton South: Cordite Publishing.

Dening, Greg. 2009. “Writing: Praxis and Performance.” In Writing Histories: Imagination and Narration, edited by Ann Curthoys and Ann McGrath, 138–158. Clayton: Monash University ePress.

Derrida, Jacques. 1982. Margins of Philosophy. Translated by Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

———. 1983. Ghost Dance. Directed and produced by Ken McMullen.

———. 1995. On the Name. Translated by Thomas Dutoit. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

———. 2006. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. Translated by Peggy Kamuf. New York and London: Routledge.

———. 2016. Of Grammatology. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Dolar, Mladen. 2006. A Voice and Nothing More. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/7137.001.0001

Foucault, Michel. 1970. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Translated by Alan Sheridan. London: Tavistock Publications.

Gibson, Prudence and Monica Gagliano. 2017. “The Feminist Plant: Changing Relations with the Water Lily.” Ethics and Environment 22 (2): 125–147. https://doi.org/10.2979/ethicsenviro.22.2.06

Glissant, Édouard. 1957. “Le Romancier Noir et son Peuple : Notes pour une Conférence. ” Présence Africaine 16: 26–31. https://doi.org/10.3917/presa.016.0026

———. 1969. L’Intention Poétique. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

———. 1981. Le Discours Antillais. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

———. 1989. Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays. Translated by J. Michael Dash. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

———. 1990. La Poétique de la Relation: Poétique III. Paris : Éditions Gallimard.

———. 1996. Introduction à une Poétique du Divers. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

———. 1997. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.10257

———. 2000. Le Monde Incréé. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

———. 2006. Une Nouvelle Région du Monde: Esthétique I. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

———. 2017a. “Nothing is true, everything is living.” Translated by Alexandre Leupin. The Glissant Translation Project. Louisiana State University. Accessed March 4, 2018. https://sites01.lsu.edu/wp/theglissanttranslationproject/2017/10/20/nothing-is-true-everything-is-living/

———. 2017b. “The poetics of the world: Global thinking and unforeseeable events.” Translated by Kate Cooper Leupin. The Glissant Translation Project. Louisiana State University. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://sites01.lsu.edu/wp/theglissanttranslationproject/2017/10/20/the-poetics-of-the-world-global-thinking-and-unforeseeable-events/

Gott, Beth. 1983. “Murnong – Microseris scapigera: a study of a staple food of Victorian Aborigines.” Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 2–18.

Hatley, James. 2000. “Recursive Incarnation and Chiasmic Flesh: Two Readings of Paul Celan’s ‘Chymisch’.” In Chiasms: Merleau-Ponty’s Notion of Flesh, edited by Fred Evans and Leonard Lawlor, 237–249. Albany: SUNY Press.

Hill, Jess. “Privilege, power, patriarchy: are these the reasons for the mess we’re in?” Guardian, October 18. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/oct/18/privilege-power-patriarchy-are-these-the-reasons-for-the-mess-were-in

Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London and New York: Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203818336

Jones, Jonathan. 2019. Bunha-bunhanga: Aboriginal agriculture in the south-east. Tarnanthi, curated by Nicci Cumpston. Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants . Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions.

Lather, Patti. 2007. Getting Lost: Feminist Efforts Toward a Double(d) Science. Albany: SUNY Press.

Lefebvre, Henri. 2004. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. Translated by Stuart Elden and Gerald Moore. New York: Continuum.

Martineau, Jarrett, and Eric Ritskes. 2014. “Fugitive Indigeneity: Reclaiming the Terrain of Decolonial Struggle through Indigenous Art.” Decolonisation: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3 (1): 1–12.

Marsh, Walter. 2019. “Jonathan Jones and Bruce Pascoe offer a timely illustration of Aboriginal lands on the cusp of colonisation.” The Adelaide Review, October 1. Accessed October 2, 2019. https://www.adelaidereview.com.au/arts/visual-arts/2019/10/01/tarnanthi-bunha-bunhanga-jonathan-jones-bruce-pascoe/

Mitchell, Thomas. 1839. Three Expeditions into the Interior of Eastern Australia; with descriptions of the recently explored region of Australia Felix, and the present colony of New South Wales, Vol. 1, Second Edition. London: T. & W. Boone. Accessed November 27, 2020. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.33129

“The Murnong Story.” 2019. ABC Education. Accessed July 14, 2020. https://education.abc.net.au/home#!/media/3123864/the-murnong-story

Nancy, Jean-Luc. 1991. The Inoperative Community. Edited by Peter Connor. Translated by Peter Connor, Lisa Garbus, Michael Holland, and Simona Sawhney. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

New South Wales Government, Department of Primary Industries. 2020. “Native Millet.” Accessed August 27, 2020. https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/agriculture/pastures-and-rangelands/species-varieties/native-millet

Pascoe, Bruce. 2014. Dark Emu, Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? Broome: Magabala Books.

———. 2021. “Farming Futures: Bruce Pascoe in Conversation with Ash Elliot.” Wonderground 1: 126–131.

Puig de la Bellacasa, Maria. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ricœur, Paul. 1985. Temps et Récit III. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

———. 2003. La Mémoire, l’histoire, l’oubli. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Rose, Deborah. 2004. Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics for Decolonisation. Kensington: University of New South Wales Press.

———. 2009. “Writing Place.” In Writing Histories: Imagination and Narrative, edited by Ann Curthoys and Ann McGrath, 184–210. Clayton: Monash University ePress.

South Australian Seed Conservation Centre. 2018. “Panicum decompositum var. decompositum (Graminae).” Seeds of South Australia. Department for Environment and Water, Government of South Australia; Botanic Gardens of South Australia. Accessed September 14, 2020. https://spapps.environment.sa.gov.au/SeedsOfSA/speciesinformation.html?rid=3206

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofky. 2003. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822384786

Serres, Michel. 2003. The Natural Contract. Translated by Elizabeth MacArthur and William Paulson. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

———. 2014. Times of Crisis. Translated by Anne-Marie Feenberg-Dibon. London: Bloomsbury.

Simpson, Jane and Luise Hercus. 2004. “Thura-Yura as a Subgroup.” In Australian Languages: Classification and the Comparative Method, edited by Claire Bowern and Harold Koch, 179–206.. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.249.12sim

Spahr, Juliana. 2011. Well Then There Now. Boston: Black Sparrow Books.

Verass, Sophie. 2018. “This native superfood is 8 times as nutritious as potato and tastes as sweet as coconut.” SBS, February 27. Accessed August 17, 2020. https://www.sbs.com.au/food/article/2018/02/27/native-superfood-8-times-nutritious-potato-and-tastes-sweet-coconut

Vieira, Patrícia. 2015. “Phytographia: Literature as Plant Writing.” Environmental Philosophy 12 (2): 205-220. https://doi.org/10.5840/envirophil2015101523

Watson, Judy, and Louise Martin-Chew. 2009. Judy Watson: Blood Language. Melbourne: Miegunyah Press.

Dr Camille Roulière is an early career researcher whose work explores how humans engage and interact with their environments through art. In 2018, she was awarded a University Doctoral Research Medal for her PhD thesis entitled “Visions of Water” (The University of Adelaide). Camille also works creatively with a variety of materials, from words and musical notes, through to glass, metal and acrylics. Most notably, her work has been published in Southerly, Cordite Scholarly, Art + Australia, Meanjin and an anthology within Routledge’s Environmental Humanities series. She is currently co-editing a collection for Routledge (with Claudia Egerer, from Stockholm University) and has pieces forthcoming with Shima, The Saltbush Review and Wonderground.

© 2021 Camille Roulière

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.