Speculative Space

Anke Haarmann and Alice Lagaay

with Torben Körschkes, Frieder Bohaumilitzky, Tom Bieling,

Barbro Scholz, and Petja Ivanova

and drawing by Stephan Kraus

Speculative Space on stage at the Problems of Performance Philosophy conference in Helsinki June 2022

Here we are together on stage. Sitting on chairs, each in our own spot, with a certain distance between us, creating a constellation in space. What’s going on here? What’s being addressed? What are we negotiating? And by what means? As in astrology, lines of connection can be drawn between each position or point on the stage; can be interpreted into a composition to tell a whole story, a story of the whole, even when, in fact, there may be no actual lines. In the background behind the stage, building a backdrop to the scene, a film is being projected. It’s a film we made about our work and our lines, or breakdowns, of connection. It’s our film. It shows how everything is mixed up. It’s not always clear who’s who in the film. The camera circles around the table in our work lab, where we can now be seen sitting, standing, or lingering. The camera oscillates between movements and close-ups. The images sometimes dissolve into motion blur, animations appear as visual comments on what is being said: a butterfly, a ball with scribbles, a crooked handcart—not drawn or pushed, but driving in circles as if by magic. We move in circles too, between our individual points of view and our collaboration in process. One drops into the mix, forgets oneself for a time while thinking something through with the others; then we merge for a moment in concentration until someone gets hungry or needs a break, and then each of us steps out of the gathering, reconstituting a singular entity, creating distance in order to reconsider.

SpecSpace sitting around the wobbly table at the Centre for Design Research, HAW Hamburg. Still from Zones of Entanglement, film made by Tamara Hildebrand and Stephan Kraus, HAW Hamburg 2023.

You see us in the film, sitting around a wobbly table,[1] discussing our work. We are discussing the constellation of our positions in a joint research project that seeks to move beyond conventional, orderly, “sorted out” formats of research, to include the mixed-upness of our work, our quest to expand the disciplinary register to include its aesthetic and performative dimensions. We come from philosophy, political science, art, and design. The aim is to investigate, try out, test, and lay new foundations for experimental artistic research. In the film we are tangled up, but on stage we are distinct. We are thinkers, each one of us a hybrid of various disciplines and realms of expertise, and we are arguing for hybrid constellations in which speculation may unfold as an epistemic practice in the planning and drafting of things and texts. We think and argue about hybridity, but our actions, are they really hybrid? In the presenting of positions and through the performative negotiation of constellations, the question gains contour, becomes palpable, intensifies. The question becomes real.

We think and argue about hybridity on stage. In the presentation of positions and the performative negotiation of constellations, the problem takes shape. It becomes tangible, it intensifies. The problem becomes real. But why do we have this problem? Why do we have a problem with hybridity?

After the crisis of “grand narratives”, in the face of doubt in truth, in the aftermath of the terror of “clean” ideals, we have looked to the hybrid as if for salvation. In an apparent legacy of the ‘Enlightenment’ (with a big E) the assumption was that knowledge is universal and that all societies and cultures are knowable from a singular bird’s-eye point of view. This has resulted in what some might call a ‘tyranny of logic”, the boundary-defining framework of science that excludes any episteme that cannot be grasped by its methodological norm, defining thereby what can or cannot constitute the “knowable” or “true”. The same generalising framework also defines what is regarded and valued, what counts, as knowledge in the first place. The focus tends to be on the communicable (and therefore marketable) outcome, the “results”: ideally discrete nuggets of information that can, in principle—or so it is assumed—be further digested and imported into other contexts, independently and regardless of the actual embodied processes that led to the original formulation of these results, and regardless of the original (and local) context in which their significance might be embedded. Related to this are the challenges of post-colonial thought. In particular, the fact that any effort to think through and to overcome the violence of exclusion, implied and continuously enacted by the academic straitjacket, faces the problem of how to define and reframe what constitutes knowledge and truth as opposed to, say, belief, dogma, ideology or mere speculation. Increasingly, however, “rebellious” epistemes are emerging on the fringes of academia, demanding, for instance, that more subjective, non-quantifiable experiences (as opposed to strictly empirical experiments) be equally valued as knowledge.

It is understood, of course, that knowledge is political and that philosophy is no longer just spirit, but embodied thought; not mere abstraction, but action. In recent years, especially in the context of artistic and design research, the focus has moved from science (“Wissenschaft”) to research (“Forschung”), and thus from knowledge to process: to process, understood as an approach that does not seek answers as much as the formulation of problems; involving a methodology that is no longer “purified” (to take the form of a singlular “result”), but accepts incompatible perspectives and inconsistencies, tolerates, and at times even welcomes, a certain blurredness…. Hybridity, as opposed to interdisciplinarity, is the mixing of disciplines, the crossing of ideas with bodies, the forbearance of fragmentation in the unfinished, the celebration of ruptures, the defense of essayism in the face of the system. And hybrids do not multiply in conventional ways, not straightforwardly; they do not constitute tradition or stabilize in the identical—as such they are in part necessarily un- or non-disciplinary, perhaps at times even necessarily dilettantish.

In the academic context (unlike elsewhere), however, this salvatory idea of hybrid thinking, the emphasis on collaboration, is initiated in the abstract. The hybrid is above all a discursive topos, hence, an idea and maybe not a reality. We have imagined a world of hybridity in its absence. It’s a colourful world, full of diversity. One that does not discriminate, but welcomes and seeks to integrate, or at the very least, to acknowledge. This hybrid world is not dialectical but plural, not one of assimilation but of addition. Imagining worlds as these is essential in order to overcome traditions and to draw thought onto new tracks. But are hybrids really so gratifyingly “additive”, so positively generative of meaning in a constellation in which each position takes the other(s) into account? In our collaborative project, are we (and our various interests and expertises) bobbing along happily in a stream of interested togetherness? Do we really reside in this “entangled zone”? Is this how one becomes hybrid? Are we doing this work harmoniously in a mode of diversity together, or not rather, at times at least, against each other?

And this is where our problem starts: Because if we take these more subjective, non-quantifiable experiences and their hybrid entanglement seriously as reference points or sources of inspiration for other forms of knowledge, and if we conduct research accordingly with many subjectivities and diverse experiences, trouble arises, at least if we really take the plurality of subjectivities seriously as distinct embodied experiences. To carry out research in a constellation with many—which we might want to call neither collective nor transdisciplinary but hybrid—opens up a plethora of questions. Not only the question of how best to define the hybrid, but also the question of the type of knowledge that is developed, and above all the question of the compatibility of the many subjectivities in this hybrid constellation. Whilst a neutral, transparent, and universal truth may be a fantasy construct, the disturbance of such a construct through individual embodiments is no simple alternative. It requires a careful observation of the modes and assumptions, the premises and processes of different knowledge-generating practices within the confines of academia and beyond. In other words, how do we work together once we have acknowledged and accepted our differences as difference?

Addressing how we work together requires that we portray how we work individually. Depending on the type of work involved, and also, perhaps, on our individual personalities, our approach to this self-analysis is particular in each case. Some of us, for instance, will describe the practical and strategic methods used to develop concepts for design projects: building with ready-mades, identifying dichotomies, juxtaposing and contrasting contexts, enhancing paradox. Others will deliver a close phenomenological description of specific skills involved in various phases of their work. These skills are invariably implied in the idea of what our work “is”, but not usually considered as contributing significantly to its outcome; not normally worthy of mention or attention. A close observation of the actual processes involved in carrying out certain everyday work tasks—speaking, writing, experimenting with materials, listening, waiting, doubting, procrastinating, warming up, reading, re-reading, editing, reading out, going for a walk, marinading, starting over, collaging, connecting, refashioning, sewing, letting grow, feeding, etc.—suggests, however, that these tasks are not just subsidiary methods or neutral service providers, as it were, but in fact intricately and methodologically involved in the creative process of researching, especially when highlighted by the sensitivities of a performance philosophy paradigm. The action of observing and describing what we actually do as we carry out our daily work is understood here as an essential methodological step in the infinite process of situating and localizing our artistic research practices, a process which must necessarily accompany, and be valued equally to, the connected and infinite process of enlightenment (with a small e).

In the context of our performance on stage at the Performance Philosophy conference, the aim was not only to reflect on subjective and embodied experience in multiplicity, but also to locate and perform it physically and spatially. This is where the limitations of this text become apparent. In Helsinki, physical experiences on stage and positions on research practices were spatially given. Speech acts were characterised by postures and body movements, and the whole scene was set against the background of a film. The cinematic layer was part of our live presentation, during which it rhythmically interrupted our individual positions on stage, demonstrating the continuous oscillation between individual manifestations and negotiations of artistic thinking and group entanglement. The aesthetic dimension of this presentation and reflection on the stage of the “Problems in Performance Philosophy” conference was crucial: its performative, spatial, temporal, situated, physically present, and cinematically represented nature. Not only does it reveal itself in the doing, but there seems to be a sense in which it requires the liveness of performance, which intensifies its presence, for further layers and dimensions of autopoietic entanglement to become perceptible to us—if not also to the/an audience.

What follows is an attempt to approximate a repetition of this oscillation in writing, i.e. on the “stage” of the Performance Philosophy journal in contrast to the stage of the performance philosophy conference,[2] of the experience of “performing” an idea of our work on stage, in a theatrical setting; and a reflection of the emergence of “zones of entanglement” between us—that came about through and as a result of the heightened awareness generated by the very act of “performing”.[3]

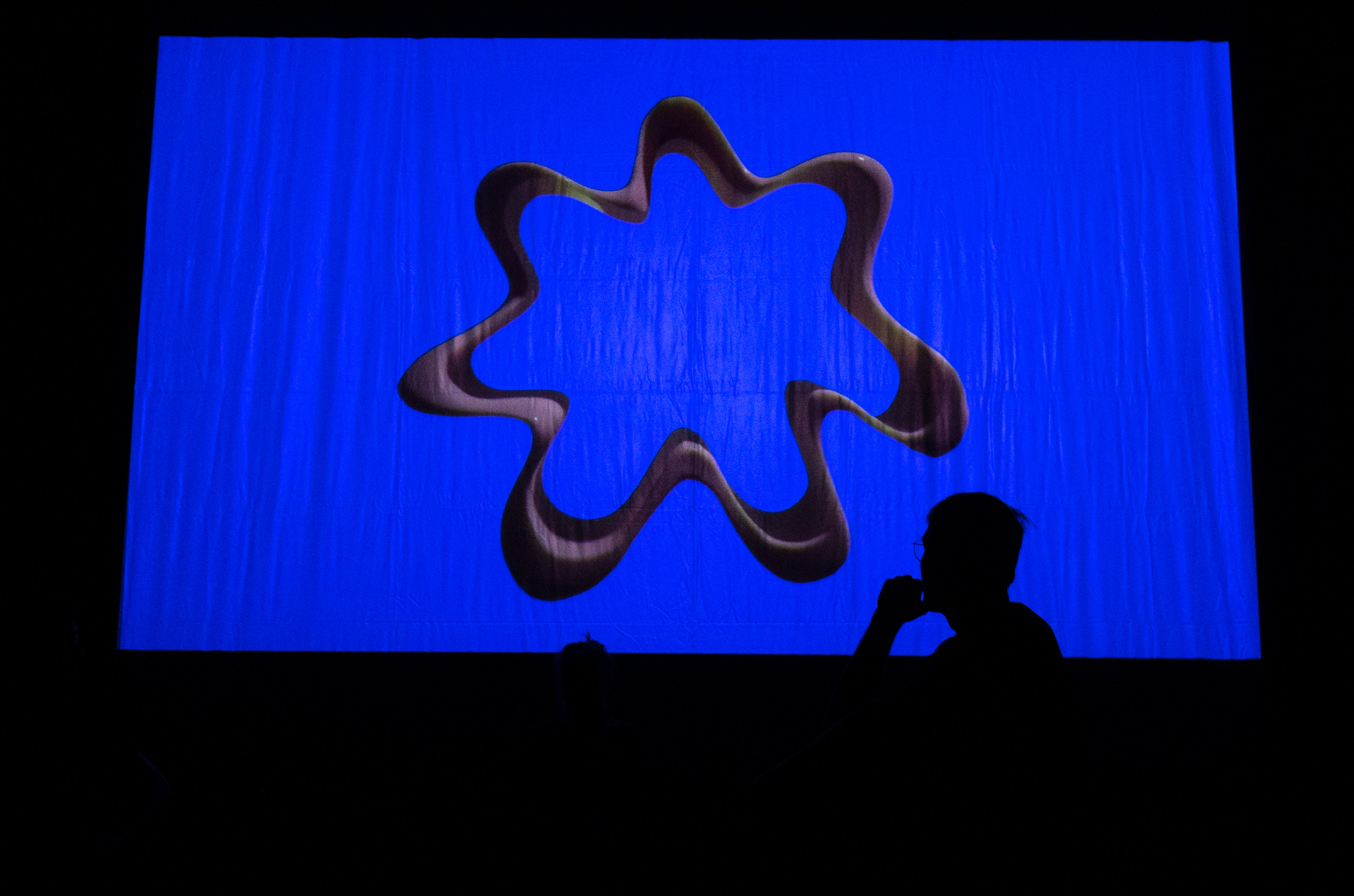

Torben Körschkes on stage with a projected animation of the "zone of entanglement" during the Problems of Performance Philosophy Conference, Helsinki June 2022.

I work with semi-finished products. Semi-finished products are intermediate products that are manufactured for further processing. A plastic tube, for example, can be a semi-finished product made from synthetic material in order to be further processed into furniture. On the one hand, the semi-finished product already points to the finished product; on the other hand, it always contains the possibility of becoming something completely different—the potential for bends and new connections, a speculative moment. In its not-yet condition it refuses to be fixed. The semi-finished product consists of only one material, and through this it refers unabashedly to its own history. At the same time, it does not establish an identity through this reference to its origin. The semi-finished product is “becoming”; it invites us to discuss the question of its completion over and over again. For practical reasons today—because material semi-finished products are more difficult to transport than immaterial ones—I propose that we consider language as the raw material, as both a semi-finished product and s an artefact. Letters, grammar, terms, sentences, sentence connections that meet in a given context, are interpreted differently in another context, generating new possible references. Concepts, too, communicate a certain meaning, but they can also pivot on the way to gradually completing this meaning. It is a matter of poetics, that is, of the re-connection of the sign network.

I will now read two passages from a book on Tai-Chi and replace the term Tai-Chi with the words “Working Together”:

Being an art embracing the principles of physiology, dynamics, psychology and moral life, Working Together cannot be mastered without long and constant practices, nor can its intricacies be fully explained in words. In the practice of Working Together, one’s bodily movements have to be soft, slow, regular, and natural. However, it causes perspiration, after which one breathes normally instead of feeling exhausted. […] Above all, the nerves in the skin will be so much improved in sensitivity as to be capable of locating other people’s center of gravity and places of strength and weakness, and of even feeling the pressure of air. (Chen 1971, iii)

All the movements, both with and without outer forms, are composed of circles. These circles may be plane or cubic, straight or slanting, big or small. They make complete circles when they are big and become points when small. When used, the circle or point should be distinguished as to Yin and Yang, softness or firmness, that is, partly neutralizing and partly giving attacks. Moreover, a circle may be made from a point, and any point on that circle may form another circle; in this manner the process may go on infinitely. The higher the level in the art one attains, the smaller are his or her circles, which do not show in an outer form. These mystic principles can be thoroughly comprehended only by those who have attained a good level in Working Together. A beginner needs only to know that every movement contains a circle, or circles. (Chen 1971, 8)

In the film projected behind us on the screen on the stage, a circle may be made from a point, and any point on that circle may form another circle; the process may go on thus indefinitely. It is through this exercise that we first arrived in the “Zone of Entanglement”. We made a first circle and discussed ways of working together, next to each other, opposite each other, for each other: in a film that shows the laboratory we have put ourselves in. The conditions of the laboratory were an elliptic table that at once drew us together and maintained a safe distance. The elliptical shape of the central meeting table refers to Aby Warburg, who saw a moment of liberation in this geometric form. For Warburg, Johannes Kepler’s discovery that the orbits of the planets are not circular but elliptical constitutes an “emancipation from traditional patterns of thought and topoi” because it takes away the center of thought.[4] The conditions of the laboratory also included: a variety of fruit and biscuits that put us in a good mood but also revealed individual preferences; the timespan of an afternoon that we had agreed to let ourselves be present for, but that would also be foreseeably over at a given time; a mistress of ceremonies who, as a moderator, led us, asked questions, offered feedback and let us play; and an observation apparatus—the camera—that both disciplined us and invited us to flirt with it. Thus equipped, we talked, conferred, provoked, tussled and quibbled, interpreted and analyzed, engaged and disengaged; we would turn towards and engage intensely with each other for a while, then lean back, drift off, walk away. Visual material and recordings from that afternoon at the round table were examined, sifted, segmented, sorted, grouped into themes, stylised, and assembled until a story around “Zones of Entanglement” began to emerge and take shape: the film. The film itself forms a new circle, a video loop, into which yet other circles are let in. These further circles are now positions that we assume individually, ones that distinguish us, through which our differences manifest. In a sense, the provocation of these differences is made possible and sustained by the shared video footage of our negotiated collaboration. The film stretches seven times, yawning mightily, as it were, and our seven different positions emerge from this yawning gap, becoming visible one after the other.

I am interested in current discontinuities in dispositifs (Foucault); in what happens when two dispositifs meet. What contradictions arise, what follows from them, and how can they be made discussable? I understand discontinuities not as simple ruptures but as the place where contradictions become apparent. In my practice, I always start from one field and observe how it collides with other fields, how it is absorbed by them, or how both merge into each other. The field I start from is the field of art, design, theater, architecture—in sum: the field of so-called creativity. I use the contradictions that arise in the clash of the creative with other fields as an entry point to speculate with design. When the practice of the creative encounters other rationalities of action, this usually says something not only about the supposedly other dispositif, but also about one’s own field of practice, which can thereby be critically interrogated. The sharpened contradictions are not absurd because the speculation might twist something, but because contradictions in one’s own action are brought before one’s eyes.

By means of an example of my work: In the announcement of the minister of defense to redesign the parlours of the Bundeswehr to make the army more attractive as an employer, I observed the clash of the military dispositif with a creativity dispositif, in which “previously marginal ideas of creativity have been elevated into an obligatory social order”. I used this to speculate about what might happen if the locking-up and disciplining mechanisms of the military dispositif were subjected to the self-actualizing principles of the creativity dispositif. After carrying out a series of workshops with soldiers, representatives of the Ministry of Defense, and employees of the Bundeswehr’s in-house consulting department, I translated their wishes into exaggerated designs for the parlour.

So, do the contradictions between one’s own and the others’ position, the assertion of a hybrid collaboration and the stating of individual points of view, cease to be painful because they are now made present in a designing space, a space of possibility, and thereby find a new form? The space of possibility is held together by the intensity of presence, but also by the viewing audience and the speculation that arises through them with regard to other forms of the self. Through speculation on the possibility of hybridity, we are called to look at our methods with fresh eyes. What do practices that are concerned with the possibility of fusion and entanglement, with the mixed together, actually look like? What goes into them? What does it take to sustain them? How might we even begin to think and design when the very process of searching requires one to first discover a process for understanding this unfolding practice in the first place? How are we to imagine the creative, productive, risky practices of this understanding?

Souvenir created by Stephan Kraus to accompany his sound file for the Specology edition (2023). For more please go to http://www.speclog.xyz.

I don’t know if I really have a method; things would certainly be easier if I did... especially for the people around me. It would be easier to see what I’m doing. But I’m also a great believer in throwing all method to the wind. I need to do so in order not just to repeat but to tend towards, to attend, to attune to what’s going on, what presents itself…. It’s not the application of a method or a program, if anything it’s a—sometimes seemingly pathological—waiting, bearing with, holding out, not doing, until an impulse, or the fragment of a sentence begins to form. And then, well then, I need to talk it through, even if it’s only to mumble to myself. And then, hopefully, eventually, a kind of rhythm is found. Things begin to fall into place, although it’s a lot about hesitating, residing undecided on the brink of a feeling for the formulation of a thought. Until, I don’t know, it’s as if gravity were involved: like snow falling off a leaf, all of a sudden something is said. This vocalization feels also like a kind of invocation, a plea, a conjuring act…. It’s a drawing into presence, not of something necessarily already existent, but perhaps, of a possibility. I like this thought, at the opening of Robert Musil’s Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften (The Man Without Qualities, 1930), the evocation—perhaps also invocation—the calling into the realm of the sayable, of a thinking not bound to the real, but open to the possible. If there is, he writes, a “Realitätssinn” (the sensing of reality), then there must also be a “Möglichkeitssinn”: a sensing of the possible.

And from here it’s certainly as if the invocation were to have the grammatical structure of an address, of a calling—perhaps, in another register, one could say of a prayer…. A prayer, for instance, for recognition of the fact that there are many things that we do not know, including essential things. (And a prayer, therefore, for hesitation, in order that one might reach clarity in understanding what is not known: for must one not strive for precision in recognizing what it is that one does not know?) And a prayer for trust and confidence in dealing with and holding space for the uncertain. (For one need not always oversee and control everything…. I can allow myself to indulge in a certain pleasure of uncertainty.) And yet, for this to be possible at all, one must surely trust one’s own intuition, fragile though it might be, the perception of an inner voice, the voice of instinct and critical intuition, as well as its potential for subversion and transformation—the voice of conscience?—even and especially when working in a collective.

But what does it mean to trust one’s own intuition, even or especially when it comes to working collectively? What is the inside of this voice that claims to be the bearer of my intuition? Is it really ever one’s own? Socrates refers to an inner “daemon” that guides him in the process of decision making and serves as a moral compass (“a sort of voice that comes to me, and when it comes it always holds me back from what I am thinking of doing”; Plato 1914, 115). This idea of a voice from beyond that, merges with the subject’s inner sense of self, is a recurrent theme at the dawn of Western philosophy. Diotima, for instance, is a figure who intervenes and offers wisdom but is not herself seen. Speaking through Socrates in the Symposium (Plato’s staged discussion of love [Plato 2022]), Diotima marks the transition, the hybrid between abstract reasoning and concrete voice. She can be seen, perhaps, as a paratype, a somewhat crazy model for hybrid thinking. Doesn’t intuition, then, make the other, the internalised outsider, intelligible? And what possible articulation can we make of this?

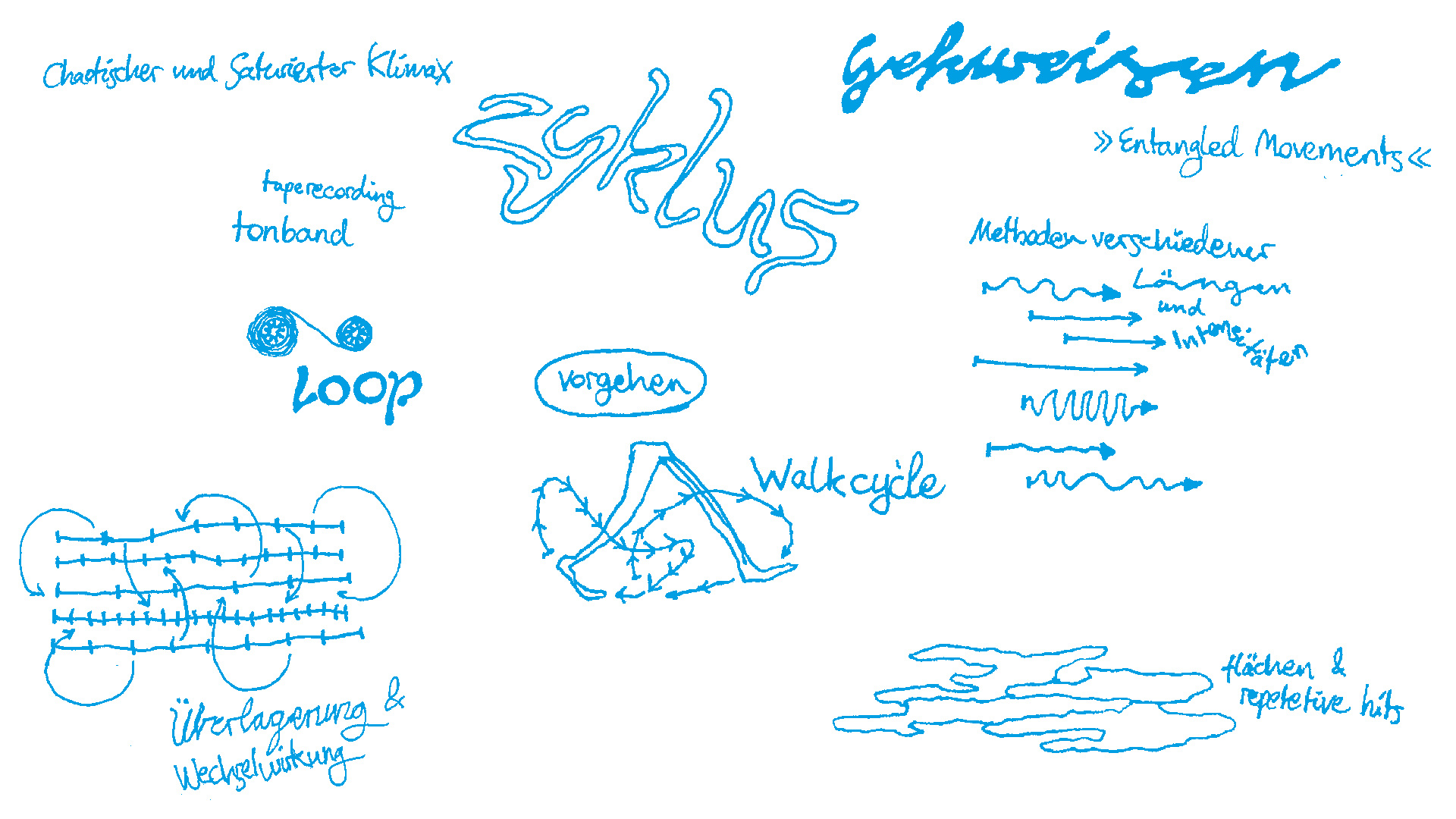

Recherche automatique and illbient research:[5] Especially the early phases of my investigations sometimes remind me—at least partially—of the processual structure of écriture automatique.[6] In other words, a procedure in which inputs and expressions (of any kind) are brought into a pre-argumentative form largely raw and unpolished and in any case on an equal footing with each other. The writing, creative, sketching, visualising, sometimes even tinkering, process of searching for contexts of meaning deliberately eludes premature control of meaning at this stage. This also means that what is supposedly erroneous (whether orthographically, argumentatively, content-wise, visually or formally-aesthetically) is not only desired, but often proves to be purposeful. It is precisely the “genre violations” that happen in the process that turn out to be groundbreaking, refreshingly enriching and—of course—sometimes also confusing and seemingly desperate. In my self-perception, I notice time and again that more seems to be involved than mere cutting and sampling techniques in which different elements are mixed with each other, but that they are once again superimposed on everyday realities, emotions, thoughts and what was previously not perceived at all or only subtly, which in turn awakens new strands of meaning, significance and argumentation. It’s comparable to a sound or song structure that arises solely from the fact that I stroll through an urban landscape with music in my headphones and an independent, unplanned, perhaps temporary, but nevertheless true sound emerges from the cacophony of song/track, engine noise, babble of voices, and birdsong. Especially during a pandemic or when working more from home, this can also mean, for example, that lines of connection to the everyday can be traced in the researching activity: from small talk with the postwoman in the stairwell to helping kids with their homework, or from the children’s play, their painting and building technique, to a toilet reading or the question of what we are going to cook tonight or how we are going to coordinate daily routines for the coming week: an atmosphere of sounds, thoughts, reflections, disputes, questions, and impressions, intrinsically linked to a certain place, a room, or a situation, in any case: the opposite of silence—seeps into the research.

The research, the thinking, the writing of text is infected by experience. Its quality is rational-aesthetic. Upon careful inspection, one’s own practices, those that feel like they belong to and best reflect oneself, turn out to be intrinsically mixed up with others. I might not listen to music, I might rather be one to get lost with myself in the garden while pulling out weeds. But this difference amounts to a form of kinship, for I, too, come to recognise that my very own collage of experience, between everyday life, concreteness, abstraction, writing and tactile practice, constitutes more than a mere parallelism of the dissimilar. Meaning is generated in the very superimposition or collision of layers. And during our performance at the conference, as we stood there exposed, in the urgency of live embodied presence on stage, our attention was provoked in ways that we had not experienced before and suddenly we saw connections beyond the acknowledged methods of thinking and designing, correspondences between our individual positions that we had not been aware of until then. But this could result in an undermining of the difference between conceptual reflection and aesthetic design practice, because in all these procedures, the aesthetic and the conceptual, the concrete and the abstract, the inner and the outer overlap and only the subsequent modelling of the process highlights one or the other—but why?

Barbro Scholz exploring social space and illuminating Anke with wearable lights during the Problems of Performance Philosophy Conference, Helsinki June 2022

What is the aesthetic experience of wearable light beyond tech fashion or blinker jackets? My research combines material design with somaesthetic interaction design. So, one part is the actual designing of material composites that have a structure, a tactility, a physical shape and an intangible volume, a light colour, an interplay of shadow, projection, body and surrounding. The other part is the body related interaction, the idea of bodily knowing, the awareness of the interplay of body and mind, especially when it comes to interaction of body and (interactive) material. I apply material speculation to explore the bodily experience consisting of physical and intangible materials on the body. Material speculation? Material speculation is a critical tool, materializing the speculation into the possible. I investigate possible socio-cultural implications when humans become light sources.

I walk around, like this, arranging the others (my colleagues) in a circle.

I open the jacket, take it off, and walk around the others, shine light on them.

What happens here, I ask, in the human-to-human relation?

Here I stand, interacting and illuminating you with my lights, circling around you, playing with shadows.

I put my arm on your shoulder.

Is this still playful or is it encroaching?

For a moment you are blinded by me. If I turn my head in the wrong direction, I am blinded by myself.

Are we both part of the interactive material composite now?

Now I walk away from the others.

This volume around my body, this light space, could it be my shelter?

I sit down. I could never leave the light space.

Petja, come join me!

Petja Ivanova reading Frieder’s horoscope on stage at the Problems of Performance Philosophy Conference, Helsinki June 2022

Sometimes called “The House of Purpose” in astrology, the Ninth House is the house of the higher mind, study and moral reasoning. It is associated with these basic concepts: higher education, scholarship, morals and ethics, spirituality, philosophy, logic and reason. It is also correlated with secondary concepts such as broadcasting, luck, publishing, international travel.

Torben has Scorpio in the Ninth House. He likes long voyages, especially by sea.

Frieder was born with Gemini in the Ninth House. He is logical and careful when choosing his path in life. People with this constellation are pragmatic, no matter what’s happening around them. If they decide to perfect themselves, they can change their direction in life more than once, looking for success. They need their religious and philosophical views to be practical and to show logic. More than this, these natives love to write and to discuss philosophical matters. Their beliefs are usually logical and they’re constantly questioning facts.

Alice’s sky shows Venus and Uranus in the Ninth House. In an astrological chart, Uranus is an energy of randomness that opens the door to infinite possibility. No matter where Uranus is found, be prepared for change and transformation—and certainly stay on the lookout for major upheavals. The presence of emotive Venus in the brainy Ninth House of a zodiac chart indicates a love of learning and an endless thirst for new information and new experience. One possible challenging aspect of Venus in the Ninth House is an endless desire to keep exploring, keep wandering.

Barbro is born with the Moon in the Ninth House therefore highly focused in her profession. You do not need doses of motivation to grab opportunities. You are creative, imaginative, and bring a smile to people’s faces. Thus, you are trustworthy and will never betray anybody for selfish interests.

Anke is born with Uranus in the Ninth House. It’s the sign of a rebellious nature and intense philosophical thought. You are burning with brilliant new ideas, many of which may be seen by others as experimental or even fringe. Aspects of life that are traditional tend to bore you, and you’re far more excited by the potential of broad, sweeping changes and beneficial social movements.

On stage the register shifts to a guided aerobics exercise class. (Abrupt transitions are indeed part and parcel of the collective work; they stimulate the urge to draw lines and make connections.) We are called to activate our breathing and to move our limbs. Can the instructions be addressed to the readership now?

Please feel invited to stretch your neck to one side, then to the other, lift up and drop your shoulders, rotate your hips....

Are you still receiving? Can you still read? Is this an invitation or an awkward command?

Petja leads an exercise unit for SpecSpace (despite certain reservations on the part of some participants) on stage at the Problems of Performance Philosophy Conference, Helsinki June 2022

Resistances take shape. If the discourse on astrology and its path of relatability in the constellation of the stars was met with a certain distrust, it now seems equally tricky to leave behind the familiar realm of abstraction through conceptual articulation and to resort to a display of one’s body alone for communication. The attempt not merely to assert and proclaim the mixed-upness, the hybridity we seek to address, but to allow it to become manifest, or at least to work with it, proves something of a challenge. Indeed it takes strength, and a certain self-depreciation, to confront one’s own phantasms!

Thus we begin to realise that the notion of the hybrid is not quite the “simultaneous presence of the diverse” that we had perhaps had in mind. Were we unwittingly harbouring a certain ideological idea of breeding derived from the human activity of breeding plants and animals? To take the best and most desirable of the diverse and to fuse it into a new species, purified of any undesirable characteristic: a wolf without ferocity, displaying the elegance of unbridled attention, yet not submissive, but rather family-friendly? What kind of neutralised monster would it be? Is this the ambivalent core of our problem? And as these sentences form, so too does the author of this paragraph move out of their own practice and comfort zone: they write and think stutteringly as they do so.

Anke Haarmann on stage with a butterfly animation projection and Torben's silhouette during the Problems of Performance Philosophy Conference, Helsinki June 2022

My Hunt-and-Peck Method: R, T, Z, G, H, B…. these letters mark the dividing line between the right index finger and, interestingly, the left middle finger. I observe myself writing. More precisely, typing. Typing rather than writing has become the primary method of expressing oneself. The common view that lines of argument unfold whilst one types turns out upon closer inspection to be misleading. At first it is only single letters that trace the line to the screen—finger for fingertip—and the argument dwelling in the context of the sentences seems to be a laboriously acquired long-term effect in the aftermath of this hunting and pecking on the stage of the monitor. I am asking myself where only the sentences remain—this semantic fulcrum between the overall image and the particles of which it is composed. In the process of typing, the argument recedes into the background, because the letters in their individuality move to the fore. What is the ‘n’ doing? And why does the finger hit the ‘b’ by mistake? It isn’t as if the fingers haven’t been trained in the virtuosity of typing. They are swift and have habituated the arrangement of the keys. But still mistakes are made. And the dancing of the fingers is under constant observation. What is written becomes a surprise when—after typing—the eyes turn up towards the screen. Then letters are missing or have been placed just next to where they really belong. No problem because this can be corrected. But the slowing of the process of formulation by the searching fingers, the leaps of the letters, and the distraction of thinking by the disciplining authority of grammar and orthography—all these things decouple the typing process of formulation from the coherence of thought. I realize in-between my observations that the Latin for “finger” is digitus and is thus connected to the digital. Fingers are discrete, individualised, single—detached. Searching fingers, leaping letters, authoritarian orthography—they all produce gaps in the flow of formulation. And these gaps, these blank spaces of thought, become the grounds for questioning the current words, their inherent meaning. This leads to excursions of thought, questioning the forms of words, defamiliarizations of all-too-well-known terminology. That leads to research into etymologies, formations of terms…. I realize in-between my thoughts that Deleuze and Guattari were perhaps right to diagnose the work of philosophising as the inventing of concepts. The word just written becomes an alien and develops an unexpected sense. I can watch the argument forming bubbles here. Sentences sprawl into unknown dimensions. The micro-tactics of typing turn the whole business of writing into a laborious process—marked by surprises and overlaps, in which one cannot simply progress in the spirit of the argumentation of the concept—but rather the confounding proximity of fingers to the letters as individual components of words causes uncertainties, opening up hosts of parallel universes.

This work of writing, can it really be done collectively? Is it not more a question of taking turns, of each mind picking up a thread of thought and taking it elsewhere to be untied or continued? There is an element of playfulness and willingness involved, attitudes that rely on a soft bank of trust and that cannot be generalised in principle. ‘Collaboration’ is not always a positive term, especially not in the German language where the word still tends to be avoided due to its historical connotations. One prefers to speak of ‘cooperation’, a mode in which individual discernment seems less likely to be compromised. How long will this vital critical individual potential continue to be valued? Is it still?

In the interstices of the film, we become visible as individual positions on the stage. With the moving images (and words) on the screen now slowed down to the point of abstraction and suspended in the background, the viewer’s focus shifts to the bodies in space that we are, standing in formation on the stage. One by one, we are illuminated in the spotlight, each rising individually from our chairs or remaining seated to voice our position. The presence of the bodies as discrete entities, and this new performative mode, intensify our discussion about what is one’s own singular position and what constitutes a hybrid. This tension between collaboration and distinction is provoked again and revealed by the presence we have granted, or imposed upon, ourselves: first around the table, then on stage, now in writing. In presence, the difference that strives to become hybrid cannot be overlooked or passed over. It is worked through and held together by the will to create a collaborative work and disciplined by the audiovisual recording apparatus as well as by the audience: a public that perceives and critically examines form and content.

[1] The wobbly table could serve as an example of an instance of collaborative work that is both trivial and of the essence: who unscrewed the tabletop from the frame? How and when will it get fixed?

[2] It seems appropriate to note that in both cases there is something of a resistance to the context: the attempt to transpose the process of our collaborative work to either stage requires acknowledgement of various degrees of discomfort. Both the process and the result of our work do not immediately or obviously “fit comfortably” either with the modality of theatrical exposure (which was the setting of the conference—not all of us identify or have experience of thinking of ourselves as artists or performers) or with the attempt here to translate into linear writing what was experienced viscerally and physically during the live theoretical/theatrical performance. This sense of discomfort or of not quite “fitting” (or indeed of fitting too comfortably) raises a host of interesting questions: what does it mean to “fit in” in academic terms? Does this point to discrepancies or exclusivities that performance philosophy itself wishes to address?

[3] The notion of entanglement is borrowed from Karen Barad’s use of the term drawn from quantum physics to describe the entangled nature of matter, meaning and agency in the context of agential realism (see Barad 2007).

[4] Warburg expert Cornelia Zumbusch writes: “Geometrically, the ellipse can be constructed by setting two focal points instead of a centre; the ellipse is then the path that a body describes when moving around two turning points” (Zumbusch 2017).

[5] I borrowed the term “illbient” from the music style of the same name that was developed in Brooklyn/New York in the 1990s by protagonists like DJ Spooky and DJ Olive (Cf. Katz 2012, 127ff). Based on hip hop and electronic elements, the overlaying of everyday sounds and urban background noise also functions as a significant stylistic device. Illbient—a combination of the slang term “ill” and “ambient”—thus stands in the tradition of “musique concrète”, a compositional technique in which recordings contain both recorded instruments and ambient sounds taken from everyday surroundings, which are sometimes electronically alienated through montage, tape editing, modified speed, and loops.

Modes of music production and -perception are inevitably linked to technical developments and forms of media distribution. As described by the musicologist Michael Schmidt, “Media opened music to sound, and made it universally available material for multiple collages. At the same time media puts music in the state of a constant murmuring drone, an incessant flowing” (Schmidt 2009). When I refer to “illbient research”, I do not mean research into this style of music. Rather, I want to express that no kind of research investigation is immune from being affected by external, unplanned influences. Sometimes this is in fact precisely what gives rise to something really exciting.

[6] The French term Écriture automatique (automatic writing, automatic text) describes a method of writing in which images, feelings and expressions are to be reproduced (as far as possible) uncensored and without the intervention of the critical ego. Sentences, sentence fragments, word chains as well as individual words may be written without intentionality or control of meaning. What is otherwise considered faulty in terms of orthography, grammar or punctuation can be desirable and purposeful under these conditions. The surrealists propagated this literary form of free association as a new form of poetry and experimental literature. This kind of largely unfiltered “automatisation” is to be understood here as a “system of writing down” (cf. Kittler 2003), in which epistemic and aesthetic practice are interconnected.

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Chen, Yearning K. 1971. T’ai-chi Ch’üan. Hong Kong: Unicorn Press.

Haarmann, Anke, Alice Lagaay, Tom Bieling, Torben Koerschkes, Petja Ivanova, Frieder Bohaumilitzky, and Barbro Scholz, eds. 2023. Specology – Zu einer ästhetischen Forschung. Hamburg: Adocs.

Katz, Mark. 2012. Groove Music: The Art and Culture of the Hip-Hop. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kittler, Frierich A. 2003. Aufschreibesysteme 1800–1900. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink.

Musil, Robert. 1930. Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Plato. 1914. Euthyphro. Apology. Crito. Phaedo. Phaedrus. Translated by Harold North Fowler. Loeb Classical Library 36. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/DLCL.plato_philosopher-apology.1914.

———. 2022. Lysis. Symposium. Phaedrus. Edited and translated by Christopher Emlyn-Jones and William Preddy. Loeb Classical Library 166. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

https://doi.org/10.4159/DLCL.plato_philosopher-symposium.2022.

Schmidt, Michael. 2009. Philosophy of Media Sounds. New York and Dresden: Atopros.

Zumbusch, Cornelia. 2017. “Die Künste als Archive eines Ausgleichswissens.” Accessed 5 June 2023. https://www.warburg-haus.de/tagebuch/die-kuenste-als-archive-eines-ausgleichswissens.

Speculative Space was a laboratory for speculative design research at Hamburg University of Applied Sciences (HAW Hamburg, Design Department). It ran from September 2019 until March 2023 and was funded by the Federal State Research Fund of Hamburg (Landesforschungsförderung Hamburg). There were five main researchers and two associate researchers. Speculative Space initiated and hosted several design events, three lecture series, two conferences and multiple artistic/design research exhibition, most of which are documented on www.speclog.xyz. It culminated in an experimental publication entitled Specology. Zu einer Ästhetischen Forschung (Haarmann, Lagaay, Bieling, Ivanova, Körschke, Bohaumilitzy, Scholz, eds. 2023).

Stephan Kraus is a Hamburg-based sound and graphic designer and artistic researcher. His research method revolves around the creation of art objects (so-called "souvenirs") that serve as junctures for political theory, philosophy and (pop) cultural signifiers. This practice has been articulated in essays (e.g. Specology, adocs 2023 / Designabilities 2025), exhibitions (e.g. Schicht & Gewebe, Raum linksrechts 2024) and lecture performances (e.g. Zones of Entanglement, Performance Philosophy Conference 2022). He is currently involved in a collaborative project between the Academy of Creative and Performing Arts and the Department of Theoretical Astrochemistry at the University of Leiden, which aims to develop epistemological methods for artistic research in the context of natural sciences.

© 2024 Speculative Space

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.