Ash Williams, Independent researcher

People and communities are currently being exposed to a profound amount of uninterrupted grief and sadness. In my work as an abortion doula and abolitionist community organizer, I bear witness to communities mourning the losses of loved ones and fallen comrades, and mourning the loss of access to people, places, and things like healthcare, land, space, and employment. The unendingness of the current genocide against Palestinians and other groups of people around the world makes for an urgent time to mourn the dead and fight for the living. As a doula and organizer, I reflect on the performative aspects of the use of grief and mourning to bring people together, incite collective action, and create portals through which loss can be noticed and held. As a result of the interminability of the loss that many of us have been exposed to and out of the duty that we have to show up for one another in these times, it’s important that we find ways to acknowledge the ongoing loss and to create ways to support people we do our work with. By analyzing the ways that death workers and community organizers approach grief as a social phenomenon, we might better understand how to support people experiencing loss more effectively/supportively and we might learn how to transform collective mourning into collective action, so that we can better resist oppressive regimes that seek to swallow our grief and end our lives through control and domination.

Black and indigenous, queer and trans, and disabled death workers have found creative ways to invite people to grieve and process systemic forms of oppression together. These practices offer generative examples of what it might look like to traverse systemic barriers and violences in unison. The practices include inviting others to participate in grief rituals, immersions, vigils, and visioning sessions so that in our grief, we can feel connected to other impacted and sad people who feel moved by the grief. The practitioners, the mourning spaces, and the practices incite me to make connections between lack of or loss of access to housing, employment, autonomy, education, and certain forms of political power; and the loss of human life through things like the genocide against Palestinians, inequalities caused by systemic forms of oppression like white supremacy, capitalism, ableism, and unending chattel slavery. I am encouraged to consider what can be learned from frontline organizers who both respond to and hold compounded grief with and for others when holding loss and action at the center. There is something unique about the spaces created by bodies who are activated by a particular set of emotions.

We live in a society that systemically marginalizes and individualizes loss. Grievers are expected to not obsess over the loss, to move past it quickly, or do something more constructive than being sad or angry. Grievers are often made to feel that they must hold their grief alone or only in private. People place a lot of assumptions on those who are navigating loss and how they should handle things as they try to live on. In general, bereavement discourse has an impact on how loss is addressed in community settings. Some of that discourse is responsible for the assumptions that people place on grievers. Since the late 1960s, the Küber-Ross “five stages of grief” discourse has been the dominant approach used by bereavement professionals. The model was intended to highlight experiences of people diagnosed with terminal illness facing their own deaths, but the model has been misappropriated to make assumptions about how everyone moves through emotions after loss. Because of this model, it has been assumed that there is a one-size-fits-all approach to grief, which limits the imaginary possibilities of what our sadness can do. Many researchers, sad people, the people who support us, and progressive bereavement professionals have done a lot of work to undo the enclosures of discussing grief that way.

Correspondingly, I consider how much is assumed of protestors. Protestors are assumed to behave in a certain way when they condemn and decry violent people and institutions. Their movements and literal actions are scrutinized for the use of tactics that are directly confrontational and non-cooperative. The refusal of protestors and organizers is often seen as lazy, ineffective, or unproductive (which they use to their advantage). They are often given limits on how their actions are allowed to take shape, how much time they have to do them, and how disruptive they are allowed to be. Protestors do not ask for permission, however, and neither does grief. Colonization and racial capitalism are responsible for grief being regulated and remanded into the private sphere. Onlookers, settlers, and people who are not in constant grief sometimes take on a capitalist, white supremacist approach to the grieving process and what support should look like. People need access to a variety of ways to condemn and decry systemic oppression and just be plain sad or feel other emotions. Organizers and doulas invite people into portals within different proximities to loss and to each other to experience and bear witness to grieving together.

What do we have to learn from frontline community organizers about grief and loss? When a community organizer, collective, or affinity group organizes direct action, that action has the power to reverberate and multiply itself in our lives in ways that encourage mindfulness and embodiment. Out of the varying types of direct action that exist, vigils have always stood out to me due to the great deal of emotion that they convey. I consider the vigil to be a proactive response to state violence. Vigils are among my favorite types of direct actions to organize.

People who attend vigils don’t always attend other types of actions. Vigils are defined as periods of keeping awake during the time usually spent asleep and an occasion for devotional watching (OED 2023). I appreciate these literal definitions because they convey the gravity and personal connection to the watching and the witnessing. Vigils are gatherings of people held usually after someone passes away in order to offer spiritual and material relief and care for the people who are left behind. Vigils are a way to honor and remember our dead. They often take place in areas of importance to the community or the deceased person. Sometimes vigils take place at the site of death. Vigils are types of direct actions that disrupt business as usual to achieve a social and political end. They are a tool used to resist oppressive regimes.

Protestors and mourners grieve to be in connection with other people, and to honor what is important to them, to honor what was lost. When we publicly grieve, we demonstrate autonomy to live on our own terms and to mourn on our own terms (since we can’t die on our own terms). Injecting a competing story into the public arena, the vigil also functions to correct dominant narratives spun by the media and police, which is really important after someone dies at the hands of the state. Vigils function in defense of the death; they show that the person is cared about and has people who know and love them, and ultimately, that their life mattered. Vigils open up space for a range of emotions including anger, despair, and hope and they have the ability to put pressure on targets like jails, corporations, or people that cause premature death. The sanctum space is about reimagining what’s possible by speaking and connecting about what the death/ passing/ loss means for the people impacted—the greater community. With vigils, organizers and mourners exhibit a refusal to cooperate with oppressive systems by not letting the death or loss of access go unchecked and unnamed.

Memories are also shared, like at vigil for Tortuguita (Tort), a queer, Venezuelan environmental activist who was killed by Georgia State Patrol Troopers on January 18, 2023. The ongoing and collective mourning of Tortuguita signifies a transformative, communal experience of going through immense loss. Since Tortuguita’s murder, organizers all over the world have found ways to honor Tortuguita through vigil, protest, creative interventions and sometimes a mixture of all three. Many of the spaces that have been organized to remember and honor Tortuguita have included their mother, Belkis Tehrán. At a memorial service for Tortuguita in March 2023, community members and friends lit candles, shared photos, spoke, and placed a menagerie of flowers, branches, pinecones, and stones on the ground close to the Weelaunee Forest to honor the life of their friend and family member. Out of the many memorial services and vigils for Tortuguita, this one has a special place in my memory because Belkis, other family members, and loved ones spread Tort’s ashes in the forest. Many of us who continue to refuse the logics of cop cities all over the world, fight in memory of Tortuguita, and Belkis’ activism certainly provides so much loving stewardship to the people and the land that I continue to learn from.

When I think about what is lost over time in the fight(s) against oppression, I consider the people, the access, the housing, the land, the healthcare, and the freedom. I do not take it lightly that some people have lost their lives while participating in social movements. It also shouldn’t be taken lightly that the police are clearly willing to kill people who defend the forest in order to build Cop City. It is important that we remember those folks, and that we find ways to honor them for what they have ultimately given so that we can continue to undermine oppressive systems and structures.

In a Youtube video dated March 31, 2023, Belkis Tehran, Tort’s mother spoke to a crowd of Tort’s friends and comrades, Stop Cop City supporters, and the media. She said:

Be happy. Enjoy that we can continue his legacy. Enjoy that they gave us a legacy. They gave us (an) example. My wish from all my heart is that this example is alive- alive with everybody! Alive with actions, not just talking. I… I am happy. I am happy that I was blessed with such a wonderful person. Don't be sad. Don't be sorrow(ful). Because we have a life. We can give them a life. And I hope everybody all over the world knows about them. (Unicorn Riot 2023)

From watching the video it’s clear that Tort’s mother, Belkis, knows that the friends who gathered under the raindrops that day are consumed by sadness and love for Tort. She offers the mourners solace by saying “be happy.” She says Tort provided us with an example. Having met Tort only once, I knew that they were an example for kindness and love. From the stories that I’ve listened to, Tort has had a profound impact on so many people’s lives. They have immensely impacted people they met and people who only know them through death. Belkis wants the example of her child to be alive in a substantive way, a way that is about that action and “not just talking.” She reminds the crowd that we are still living and that living implores us to give them a life through our actions and what we continue to fight for and against. Indeed, Tort’s life does give an example of how to be in grief and action, and their life mattered. The way that communities all over the world mourn Tortuguita are proof of what we know. The reminder she extends about us still being alive, and still being able to enact change and struggle is inherent to the resistance against oppressive regimes. Through the performative demonstration of mourning those that we have lost, and the things we have lost access to, we can honor those people and things, and we find creative ways to keep coming together to struggle in their memory. When we struggle with our loved ones in our hearts and minds, we are connected to their commitments of disrupting state violence and we honor the lives they lived through our actions. As we mourn together, and lose people, we grow in our support of the people who are still here.

Figure 1. Unicorn Riot. Jan 21, 2023.

Figure 2. Tortuguita Vigil. Photo by @micahinatl (Jan 24, 2023)

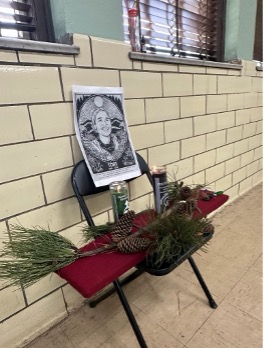

Figure 3. Remembering Tort. Photo by Ash Williams. February 26, 2023.

Reintroducing ourselves to the lives our fallen loved ones have lived is a grieving practice that can give us information about how to keep fighting and showing up for one another. It also allows for grievers and strugglers to strengthen the solidarity amongst one another by reminding us of the shared goals or ideas of the person who passed away. At a time when it seems like there are so many diverging needs or interests and a lot to get on the same page about, that kind of affinity is important. Our memory and our love for a person is often the only thing connecting the people who gather to mourn. Making a conscious and relational decision to grieve should be essential to organizing and activism.

Building altars together is another way that vigil spaces spiritual, creative, and emotional relief after a loss. Community altar builds can include gathering loved ones and community members to literally build an altar together. Community altar builds often take place in public spaces and or the place near where the death occurred. When bereaved people gather, they bring altar supplies, and throughout the time of the build, anyone who wants to can place a special item on the altar. Mourners often remember more than one person at a time at these events, and folks take time to speak their loved one’s name into the space. Memories, favorite colors, and happy and sad times also get spoken into the space. With each word, we breathe memory and life back into ourselves so that our people are not forgotten. Working with others to collectively build an altar is another opening for emotional and creative relief. The lives lived by our dead comrades come back to life as we place sacred and meaningful items, arranged like a collage of memories. Emotional relief is essential to resisting oppressive regimes because folks are having to traverse grief and show up for those who are still here, including ourselves.

In this practice of grieving out loud, we become more and more comfortable with losing important people, places, and things. We learn what to do to take care of each other after the losing. We learn about what people need in order to take a break or keep fighting. We remind ourselves that we keep us safe. We keep us safe is a reminder that communities get to determine what safety looks like for them, and that those communities do not have to rely on carceral logics or the state to co-create our visions for what safety and protection from different kinds of threats looks like. During these sacred events, people share food and bring photos, flowers, trinkets, sacred items, flags, candles, water, dirt, incense for burning, crystals, stones, clothing items, sign-making materials, and other things to write on and write with to put on the altar and have at the vigil.

When we approach grief as a social phenomenon, we can begin to extend the exploration of new opportunities that lend themselves to informing us about increasing access to grief/loss and grief/loss support. From there, we can create support infrastructures for ourselves and others. Often, organizers and care workers support with collective grief. Collective grief happens when a community, society, village, or nation all experience extreme change or loss. Collective grief can manifest in the wake of major events. Communities can experience collective grief after the passing of abortion bans and restrictions. Communities can also experience collective grief when a comrade is murdered or jailed by the police or when there are wars and genocides continuously and actively occurring at home and abroad. The ways that these types of actors show up to respond to loss and grief might be helpful for supporting people outside of the political communities that I have mentioned.

Like community organizers and death doulas, abortion doulas are careworkers who understand that grief and loss can be experienced individually and collectively. We even go so far as to establish support infrastructures like abortion doula collectives, made up of multiple doulas with a wide range of skills and abortion expertise. With the consent of abortion seekers, abortion doulas provide informational, physical, and emotional support before, during, and after abortion. We help abortion seekers navigate the many barriers to abortion care including cost, childcare, and of course abortion restrictions and limitations on bodily autonomy. We offer emotional processing and deep listening as a way to combat abortion stigma and shame. We believe that abortion seekers deserve gender-affirming care, tailored to their individual lives. We hold space for the variety of emotions that can arise when making a decision to have an abortion or simply having an abortion. Some of those emotions include grief, excitement, confusion, and anger.

Grief and loss are not the only emotions that can be present when a person is considering or having an abortion, and it is worth mentioning that abortion doulas are extremely helpful with offering non-judgmental support, listening, and increasing options for pregnant people. While grief and loss are not the only things people experience after having abortions, anti-abortion narratives and logics often lift up the impact of this emotion within a person’s abortion experience. For myself as a doula and as a person who has had two abortions, I experienced loss sure, but overwhelmingly I experienced joy, satisfaction, relief, and power. As an abortion doula, I do not assume what the people I support will feel after they have an abortion or when they are deciding. It is our undertaking to pause, listen, ask questions, and take the lead of the person I am working with. White supremacy and capitalism make people feel like they cannot grieve and that they must “power through” or “move on.” White supremacy and capitalism as world-building systems rely on individualization, quickness, and disremembering. As abortion doulas, our role is to help create space for folks to feel all of their feelings. Our role is to offer relational and slowed-down support that prioritizes what is important to each person. Abortion doulas are interested in busting binaries and bridging the gap between abortion and birth and life and death. We understand that each person’s experience is unique, and that no person lives a single-issue life. Grievers deserve this type of approach as well.

The expansive approach by abortion doulas to offer non-judgmental support and deep listening, increasing options for people who are undergoing major transitions, and not making assumptions about what people need, is essential for showing up for people who are grieving and experiencing the complexities of loss. What would it look like to approach each person’s grief experience this way? Each person’s experience with loss should be valued and honored. Assumptions about how long it will take for a person to get over a death or move past a loss can be unhelpful to the people we want to support in our communities. By connecting with others through doula-care and direct actions, organizers and doulas explore what caring for ourselves and others can look like under navigating white supremacist capitalist violence.

The tender approaches that I have shared have been developed out of struggle as well as out of the love that always already exists inside each one of our dynamic communities. How we show up for one another in the face of destruction and loss says something about the impacts we made along the way. Expansive approaches to handling people’s experiences with care are becoming more paramount within and outside of movement spaces. When we pause to consider what can be gleaned from death doula activism and organizing within the movement to stop cop city, we realize that we have an array of strategies for addressing and helping our folks move through loss. Grief is a common denominator. It is a connective tissue that holds within it the power to transform hearts and minds. What will you learn under the banner of grief?

Oxford English Dictionary (OED). 2023. S.v. “vigil (n.1),” https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/4264147725.

Unicorn Riot. 2023. “Family and Friends Gather for Tortuguita’s Memorial.” YouTube. Accessed 31 March 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UV30sbkNl-U.

Ash Williams (he/him) is a Black trans person from so-called Fayetteville, North Carolina. Since 2012, Ash’s work has included theorizing dance and performance art as tools for understanding bodies and corporeality within The Movement for Black Lives, leading rapid response and guerilla actions, particularly as an architect of Charlotte Uprising, which followed the murder of Keith Lamont Scott. This work has included co-leading a successful statewide campaign (#EndShacklingNC) to end the practice of shackling pregnant incarcerated people in North Carolina, as well as a successful campaign (#TransferKanauticaNow) to transfer Kanautica Zayre-Brown, a Black Transwoman, from a correctional facility designated for men to a women’s facility in 2019.

Making headline news in 2014, Ash disrupted business as usual at a private fundraiser for presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton, demanding that Cliinton apologize to Black people for mass incarceration, and for her racist use of the word “superpredator.”

He holds a Master’s degree in Ethics and Applied Philosophy, and a Bachelor’s in Philosophy and a Minor in Dance from UNC-Charlotte. He served as an Adjunct Professor in the Women’s and Gender Studies Department at UNC-Charlotte from 2018 until 2021. From 2022-2023, Ash served as Project Nia’s Decriminalizing Abortion resident. For years, Ash has been vigorously fighting to expand abortion access by funding abortions and training other people to become abortion doulas. Ash is also a disabled dancer, choreographer, and dance teacher.

© 2024 Ash Williams

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.