Osman Balkan, University of Pennsylvania

In September 2015 the world was briefly haunted by images of Alan Kurdi, a two-year-old Syrian child who drowned with his mother and brother while trying to reach the Greek island of Kos from Turkey by boat. The family’s goal had been to join relatives in Vancouver, BC. They set upon their fatal journey after being denied a refugee visa by the Canadian government. The heart-wrenching photographs of Alan’s small, lifeless body lying face down on the shores of a Turkish beach elicited a short-lived shift in public debates about Europe’s so-called migration “crisis.” British Prime Minister David Cameron, who had previously described asylum seekers as “a swarm of people coming across the Mediterranean, seeking a better life, wanting to come to Britain,” pledged to accept 20,000 Syrian refugees, noting that “we will continue to show the world that this country is a country of extra compassion, always standing up for our values and helping those in need” (Cameron 2015). German Chancellor Angela Merkel said that “if Europe fails on the question of refugees, if this close link with universal civil rights is broken, then it won’t be the Europe that we wished for” (quoted in Eddy 2015).

According to data collected by the International Organization of Migrants’ Missing Migrants Project, more than 70,000 people lost their lives while attempting to cross an international border between 2014 and 2024 (Missing Migrants Project, n.d.). About half of these deaths occurred in the Central Mediterranean, an area that holds the dubious honor of being the world’s deadliest border zone (ibid.). Following a series of high profile shipwrecks off the Italian island of Lampedusa in 2015, Pope Francis warned European leaders that the Mediterranean Sea was in danger of becoming a “vast graveyard” (Traynor 2014).

Widely circulated photographs of capsized boats, overcrowded dinghies, discarded life jackets, and dead bodies have all too clearly demonstrated the human costs of what Reece Jones calls “the global border regime”—a system that works to preserve opportunities and privileges for some by restricting access to movement and resources for others (Jones 2016). Such images may help spread awareness about the violence of borders. Speaking to reporters in Canada, Alan’s aunt Tima said that the world’s perception of the plight of Syrian refugees had fundamentally changed as a result of the death of her nephew. “It was something about that picture,” she said. “God put the light on that picture to wake up the world” (cit. Devichand 2016).

In response to the growing numbers of border deaths, artists and activists have staged various interventions aimed at publicly mourning, remembering, and naming the dead, engaging in what Maurice Stierl has termed “grief activism” (2016). Recognizing that individuals who die during their attempts at crossing the Mediterranean are often permanently lost at sea or, if recovered, are hastily buried in anonymous, mass graves, these “commemor-actions” seek to render visible both the structural violence of borders and the human toll of the global border regime. As Stierl argues, grief activism is a “transformative political practice that can foster relationalities and communities in opposition to a politics of division, abandonment, and necropolitical violence on which Europe’s border regime thrives” (Stierl 2016, 173). By centering the issue of death in migration struggles, grief activism has the potential to advance new forms of solidarity and to promote alternative visions of political community beyond the nation-state. The public performance of grief is a potent political force that works to destabilize the taken-for-granted nature of the global border regime, perhaps even contributing to its undoing.

This article examines three instances of grief activism connected to border deaths in Europe. My focus is on Die Toten kommen (“The Dead Are Coming”), a campaign by the Berlin-based Center for Political Beauty, Asmat (“Names”), a film by Ethiopian-Italian director Dagmawi Yimer, and Turkish visual artist Banu Cennetoğlu’s The List. Each intervention draws on different repertoires of action, performance, and critique to perform alternative gestures of mourning and memorialization that call attention to the structural violence of militarized borders and racialized membership. The Center for Political Beauty relies on public commemorative rituals like the construction of makeshift cemeteries and the staging of funeral ceremonies for deceased refugees to stretch mourning spatially by materializing burial places that connect locations and geographies that borders aim to separate. Conversely, Yimer and Cennetoğlu’s work foregrounds the importance of naming and remembering the dead as individual human beings, stretching mourning temporally through the public echo of naming the dead and keeping alive the memory of their loss beyond its sanctioned erasure. Taken together, these works exemplify the multifaceted ways in which the dead figure into transformative political projects. Furthermore, they illustrate how acts of mourning can bolster claims for more inclusive forms of citizenship and political community by destabilizing ethnocentric and territorially bounded conceptions of membership, identity, and solidarity.

My approach to the politics of mourning is informed by Judith Butler’s influential work on precarity and loss. In an essay written in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks and the onset of the Global War on Terror, Butler poses a series of generative questions about the radically different ways in which human physical vulnerability and precarity are distributed across the globe. “Who counts as human?” they ask. “Whose lives count as lives? [...] What makes for a grievable life?” (Butler 2004, 20). Their concerns stem from the observation that a hierarchy of grief and grievability informs ideas about the value of human life. This hierarchy rests on the presupposition that some lives (and deaths) matter more than others and should be protected and grieved for accordingly. According to Butler:

Some lives are grievable, and others are not; the differential allocation of grievability that decides what kind of subject is and must be grieved, and which kind of subject must not, operates to produce and maintain certain exclusionary conceptions of who is normatively human: what counts as a livable life and a grievable death? (xv)

Within this context, mourning practices are politically significant because they help delimit the boundaries of human communities. As Bonnie Honig argues, “mourning practices postulate certain forms of collective life and so how we mourn is a deeply political issue” (Honig 2009, 10).

Yet, not all losses are acknowledged as such, nor deemed worthy of public commemoration. In Butler’s view, certain normative frames mitigate against the public recognition of loss. More specifically, “forms of racism instituted and active at the level of perception tend to produce iconic versions of populations who are eminently grieveable, and others whose loss is no loss and who remain ungrievable” (Butler 2010, 24). Elsewhere, I have proposed moving beyond a dichotomous framework of “grieveable” versus “ungrievable” life by approaching grievability as a spectrum that reflects the production of a range of subject positions in death (Balkan 2016). Nonetheless, Butler’s insights on the political salience of mourning practices have been exemplified by numerous efforts to recognize and remember “ungrievable” border deaths in Europe.

One noteworthy example is The Center for Political Beauty (CPB), a Berlin-based performance art collective which describes itself as “an assault team that establishes moral beauty, political poetry, and human greatness while aiming to preserve humanitarianism” (Center for Political Beauty n.d.). The CPB has staged several public actions and demonstrations to draw attention to the violence of borders, including a high profile campaign in 2015 known as Die Toten kommen (“The Dead Are Coming”). The campaign culminated in the exhumation and reburial of Safea Jamil Deeb, a 34-year-old Syrian refugee who had drowned in the Mediterranean. Deeb had initially been buried in an unmarked grave in Sicily by Italian authorities. With her family’s permission, the CPB exhumed her corpse and transported it to Berlin. There, the group held an elaborate funeral ceremony, describing their campaign’s aims and objectives in a message posted on their website:

Every day, hundreds of migrants die at Europe’s aggressively sealed-off borders. These borders are the world’s deadliest. Year after year, thousands of people die trying to cross them. The victims of this cordon sanitaire are buried in masses in the hinterland of Southern European states. They have no names. No one looks for their relatives. No one brings them flowers.

The Center for Political Beauty took these dead immigrants from the EU’s external borders right to the heart of Europe’s mechanism of defense: to the German capital. Those who died of thirst or hunger at our borders on their way to a new life, were thus able to reach the destination of their dreams beyond their death. Together with the victims’ relatives, we opened inhumane graves, identified and exhumed the bodies and brought them to Germany.

Reactions to the event were mixed. Some German media outlets characterized the CPB’s actions as “political pornography,” while others saw in their acts “the most radical interpretation of Sophocles’ Antigone” in recent memory, suggesting that “maybe our routine, our getting used to pictures of the suffering at Europe’s external borders needs exactly such moments of shock.” The Berliner Zeitung opined that “we are being confronted with the consequences of what we do or don’t do,” noting that the CPB’s intervention “transforms refugees into people” (see Mund 2015).

Poster for Die Totten Kommen, Berlin

A few days later, the CPB staged another public demonstration in which hundreds of people marched to the Federal Chancellery to construct a “Cemetery to the Unknown Immigrants.” Some of the marchers wore black suits and carried styrofoam gravestones. Others came bearing flowers, shovels, and spades. Upon reaching the Platz der Republik, an expansive green space in front of the Chancellery, the marchers broke through police barricades and began digging ditches using all the tools at their disposal, including their bare hands. In the scuffles that followed, several people were arrested for illegally trespassing on the lawn. Nonetheless, the protestors managed to dig nearly one hundred makeshift graves, which they decorated with flowers, candles, and signs that read, “Borders Kill” and “Nobody is illegal” (von Bieberstein and Evren 2016).

In assessing the efficacy and impact of public interventions like the CPB’s The Dead Are Coming, media scholar Karina Horsti acknowledges that these events may not directly translate into a political force that would compel governments to open their borders. Nevertheless, by rendering visible a form of violence that often remains hidden, such performances help generate new, counter-hegemonic political possibilities. As Horsti puts it, “events have afterlives and critical action in the present may contribute to a politically transformative force in the future” (Horsti 2019, 6).

Others read CPB’s campaigns as acts of citizenship because they engendered new ways of acting politically and relating to one another (Lewicki 2017, 276). By foregrounding questions of borders and mourning, The Dead Are Coming brings into view “a politics of mourning without borders” (von Bieberstein and Evren 2016, 472). Such a politics works to disrupt nationalist scripts of kinship by extending grief to those outside the national community (462). Furthermore, it renders visible the complex web of relations that connect people seeking asylum with those whose governments often reject such claims. Through commemorative practices that foster radical equality—something that political institutions fail to provide—the performance of grief and mourning instigates new ways of relating to others and new forms of community, solidarity, and belonging.

A similar impulse can be seen in the works of Ethiopian-Italian filmmaker Dagmawi Yimer and Turkish visual artist Banu Cennetoğlu. Yimer left Ethiopia in 2005, arriving in Lampedusa a year later after crossing the Libyan desert and the Mediterranean Sea. He settled in Rome and was one of the co-founders of the Archivio Memorie Migranti (Archive of Migrant Memories) collective, which helps produce written and audiovisual narratives made by migrants about their experiences. The collective describes its artistic strategy as follows:

AMM’s activities are based on the use of participatory methods enhancing a multiplicity of forms of expression. Careful attention to the listening context and the quality of the speaker-listener relationship is at the core of our approach. The adoption of ‘circular’ and intersecting forms of storytelling makes it possible for the speaker-listener roles to be interchangeable. Listening is preceded by establishing a common space, sharing levels of discourse and ideals, working not only among migrants but with them, so that in representing themselves, they can be the protagonists of their stories and can master the tools of self-expression. (Archivio Memorie Migranti 2007)

The collective’s methodology sheds light on both the dialogic character and pedagogical aims of their aesthetic interventions. The works produced by AMM embody what Federica Mazzara has termed an “aesthetics of subversion.” In her view, such works offer “a new narrative around the migratory experience,” and also function as an effective way “to respond to the distortion of the ‘migration crisis’ scopic regime” (Mazzara 2019, 132).

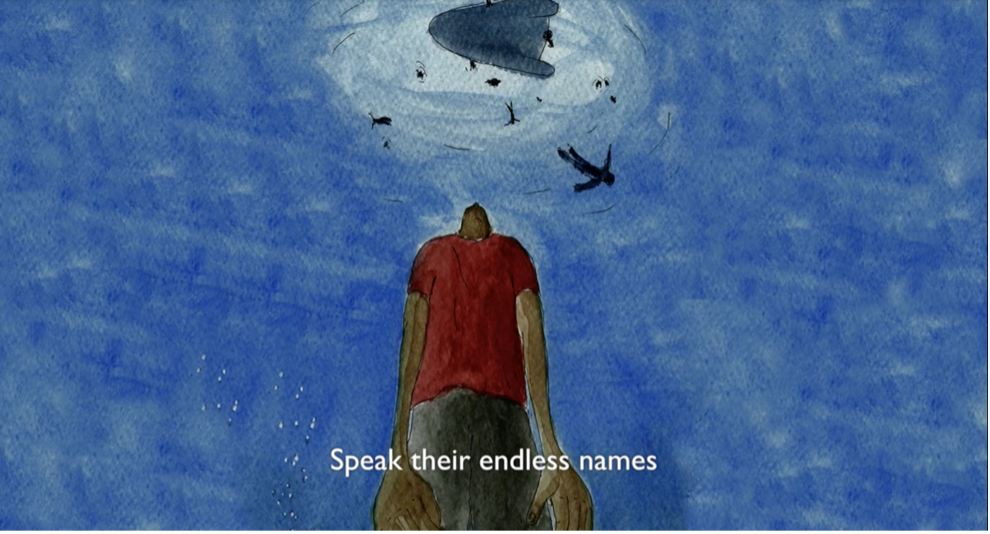

In 2015, Yimer released the film Asmat (Names), a tribute to the 368 Eritrean lives that were lost at sea after their boat capsized off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa on October 3, 2013 (Archivio Memorie Migranti 2015). The film opens with a blank screen and the sounds of gentle ocean waves. A lone female voice sings a mournful and hypnotic melody. As the screen fades from black into color, the viewer sees images of a serene, crystal-blue seascape. Suddenly, the perspective shifts to first person as the camera moves underwater, mimicking the experience of someone struggling in the water. After a few minutes of violent thrashing, the camera goes still and the image blurs out of focus. The person has drowned. A single female voice returns, softly singing the following lines:

You who are alive

are condemned to listen

to these screams.

You will not cover your ears

because our cry is loud and strong.

Nothing can stop it.

Our bodies

will land on your shores

Asmat offers a searing indictment of the political structures that lead to the loss of life in the Mediterranean. It speaks directly to government leaders in both Africa and Europe as well as to people of faith around the world, exposing hypocrisies on all sides:

You African politicians

History will remember you

as the most impotent people of our times.

You make people flee, you make them suffer

You make laws that you would not enforce on your children.

With each victim dying in the sea

You are more naked and exposed.

You European Politicians

We are here, we came here

To observe your actions

The civilization you boast of.

You believers

Who are expecting something form the sky

Don’t you see that Christ’s body is arriving from the sea?

Can’t you see God in the Other?

The narrator goes on to pronounce the names of all 368 Eritreans who drowned in the Lampedusa shipwreck. The names are spoken in the Tigrinya language and their meanings are simultaneously translated into English and Italian. According to Yimer, the intention behind the strategy of naming the dead was “to defy the attention and patience of the public, in order to bring back the numbers of the tragedy to the reality of the names” (cit. Federica and Ramsey 2019, 38). Before naming the dead, the narrator makes one final pronouncement that gives insight into what Yimer believes is at stake in mourning their deaths and commemorating their memory:

You poor parents

are condemned

to live without knowing what happened to your children.

Whether they are alive or dead.

Call them if they can hear you.

Look for them deep down.

Call them

if they can hear you.

Tell them the meaning of their names.

Speak their endless names.

There is no right time to die.

We are more visible dead than alive.

We existed even before October the 3rd

We’ve been traveling for years.

We’ve been drowning for years.

Still from Asmat, 2015.

As Simona Wright has observed, Yimer’s film “commemorates life by actualizing its absence” (Wright 2018, 91). The act of naming is at once an effort to render visible the invisible dead but also a critique of the structural conditions which grant certain people more visibility in death than in life. In Karen Remmler’s reading, the film “doubles as an indictment of the oppressive and harmful policies of neglect, outright persecution, and exclusion at the root of the displacement of migrants and refugees” (Remmler 2020). By calling out the names of the dead, names such as hope, peace, and beauty, Asmat brings into view their “now absent future lives” (ibid.), while also honoring their existence prior to their deaths on October 3, 2013. Like The CPB’s The Dead Are Coming campaign, the film instantiates a politics of mourning without borders by extending grief to those violently excluded by European border regimes. It stretches mourning temporally by extending the memory of loss beyond its sanctioned erasure, shining light on these names without bodies.

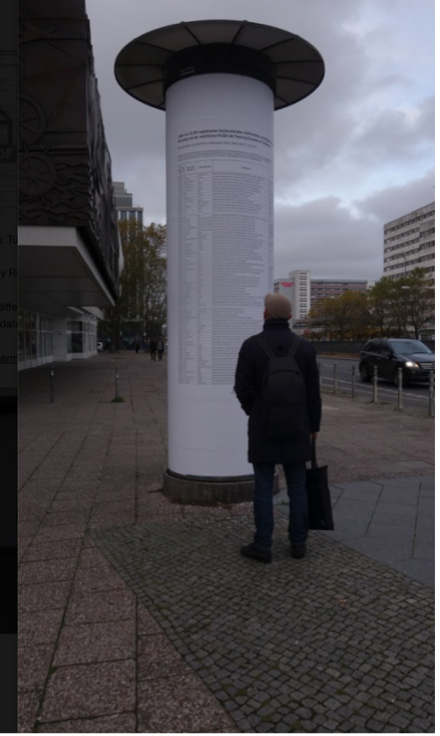

In shifting the narrative away from numbers to persons, Asmat employs a similar strategy as The List, a work by Turkish visual artist Banu Cennetoğlu. The List documents the names, genders, age, regions of origin, and cause of death of 36,570 people who perished “due to the restrictive policies of Fortress Europe” (Cennetoğlu 2019). It has appeared in a variety of forms such as poster campaigns in railway stations, newspaper inserts, and on billboards in a number of European countries including Germany, Switzerland, Norway, England, Italy, Bulgaria, Greece, the Netherlands, and Turkey. In discussing its various incarnations, Cennetoğlu notes that people relate to The List differently when it is presented as a physical object. “When you hold it there’s a way to relate to it that’s better than an infinite scrolling experience,” she observes. “When there is a screen, you have somehow the power to isolate yourself” (quoted in Higgins 2018). As a public, physical object, The List demands attention. “People should be able to see it despite themselves, and despite that they are caught up in their daily lives,” says Cennetoğlu, noting that her goal was “to put it out there without any announcement, without any direct negotiation with the audience but somehow in a negotiated space” (ibid.).

According to Cennetoğlu, the emotional power of The List lays in its ability to compel the observer to acknowledge the singularity of each death. By doing so, viewers may start to reflect upon the ways in which their own personal choices are implicated in the complex web of politics that causes border deaths in the first place. For Cennetoğlu, part of the challenge lies in making visible a form of structural violence that governments try to obscure. “Governments don’t keep these records for the public; they don’t want the public to see these records because it exposes their policies,” she says (ibid.).

Like the CPB’s The Dead Are Coming campaign, The List memorializes those whose deaths may otherwise go unnoticed or ungrieved by the wider public, seeking to give them greater visibility and legibility. By disrupting the monopoly that official powers have tried to exercise over the memories of the dead, it also challenges dominant conceptions of the nation that are limited to those that the state acknowledges and counts as its own (Keenan and Mohebbi 2020). As an ephemeral and peripatetic document that appears in different iterations across the European continent, The List functions as a deterritorialized counter-monument to the dead. For those it names, often individuals whose bodies were lost at sea or buried in anonymous graves, it serves as a “distinctive, iterant resting place” (ibid., 167).

The List, on view in Berlin, 2017.

Taken together, Cennetoğlu’s The List, Yimer’s Asmat (Names) and the CPB’s The Dead Are Coming campaign all foreground border deaths to develop critiques of restrictive immigration policies and militarized borders in Europe. Although they rely on different means and media, they coalesce around a common purpose. By honoring and remembering those who have been excluded by European nation-states, these performances and interventions problematize territorially bounded conceptions of solidarity and enact a more expansive idea of the We. The dead are central characters in this prefigurative politics and serve as a haunting reminder of the stakes of political inclusion and citizenship in a world where such distinctions can be a matter of life or death.

Archivio Memorie Migranti. 2015. ASMAT (Names). archiviomemoriemigranti. https://www.archiviomemoriemigranti.net/films/co-productions/asmat-names/?lang=en.

———. 2007. “About Us.” archiviomemoriemigranti. https://www.archiviomemoriemigranti.net/about-us/?lang=en.

Balkan, Osman. 2016. “Charlie Hebdo and the Politics of Mourning.” Contemporary French Civilization 41 (2): 253–271. https://doi.org/10.3828/cfc.2016.13.

von Bieberstein, Alice, and Erdem Evren. 2016. “From Aggressive Humanism to Improper Mourning: Burying the Victim’s of Europe’s Border Regime in Berlin.” Social Research 83 (2): 453–479. https://doi.org/10.1353/sor.2016.0037.

Butler, Judith. 2004. 2010. Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? New York: Verso.

———. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. New York: Verso.

Cameron, David. 2015. “Syria: Refugees and counter-terrorism - prime minister’s statement.” GOV.UK. Accessed 14 October 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/syria-refugees-and-counter-terrorism-prime-ministers-statement.

Cennetoğlu, Banu. 2020. The List. In Moving Images: Mediating Migration as Crisis, edited by Krista Lynes, Tyler Morgenstern, and Ian Alan Paul, 169–174. Berlin: Transcript Verlag.

https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839448274-013

———. 2019. The List. http://www.list-e.info/liste-hakkinda.php?l=en.

Center for Political Beauty (@politicalbeauty). No date. “The Center for Political Beauty is an assault team that establishes moral beauty.” https://www.facebook.com/politicalbeauty/.

Devichand, Mukul. 2016. “Alan Kurdi’s aunt: ‘My dead nephew’s picture saved thousands of lives.’” BBC News, 2 January. https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-35116022.

Eddy, Melissa. “Angela Merkel Calls for European Unity to Address Migrant Influx.” New York Times, 31 August. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/01/world/europe/germany-migrants-merkel.html.

Higgins, Charlotte. 2018. “Banu Cennetoğlu: ‘As long as I have resources, I will make The List more visible.” The Guardian, 20 June. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/20/banu-cennetoglu-interview-turkish-artist-the-list-europe-migrant-crisis.

Honig, Bonnie. 2009. “Antigone’s Lament, Creon’s Grief: Mourning, Membership, and the Politics of Exception.” Political Theory 37: 5–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591708326645.

Horsti, Karina. 2019. “Introduction: Border Memories.” The Politics of Public Memories of Forced Migration and Bordering in Europe. New York: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30565-9.

Jones, Reece. 2016. Violent Borders: Refugees and the Right to Move. New York: Verso.

Keenan, Thomas, and Sohrab Mohebbi. 2020. “Listing.” In Moving Images: Mediating Migration as Crisis, edited by Krista Lynes, Tyler Morgenstern, and Ian Alan Paul, 165–168. Berlin: Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839448274-012.

Lewicki, Aleksandra. 2017. “The Dead Are Coming: Acts of Citizenship at Europe’s Borders.” Citizenship Studies 21 (3): 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2016.1252717.

Mazzara, Federica. 2019. Reframing Migration: Lampedusa, Border Spectacle, and the Aesthetics of Subversion. Lausanne: Peter Lang.

Mazzara, Federica, and Maya Ramsey. 2019. Sink without Trace: Exhibition on Migrant Deaths at Sea [Exhibition]. P21, London.

Missing Migrants Project. No date. International Organization for Migration. Accessed 14 October 2024. https://missingmigrants.iom.int/.

Mund, Heike. 2015. “Provocative Artistic Intervention.” Deutsche Welle, 17 June. https://www.dw.com/en/provocative-artists-rebury-remains-of-refugee/a-18522573.

Pool, Heather. 2012. “The Politics of Mourning: The Triangle Fire and Political Belonging.” Polity 44 (2): 182–211. https://doi.org/10.1057/pol.2011.23

Remmler, Karen. 2020. “The Afterlives of Refugee Dead: What Remains?” Europe Now, 28 April. https://www.europenowjournal.org/2020/04/27/the-afterlives-of-refugee-dead-what-remains/.

Stierl, Maurice. 2016. “Contestations in death—the role of grief in migration struggles.” Citizenship Studies 20: 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2015.1132571.

Traynor, Ian. 2014. “Pope Francis attacks EU over treatment of immigrants.” The Guardian, 25 November. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/25/pope-francis-elderly-eu-lost-bearings.

Wright, Simona. 2018. “A Politics of the Body as Body Politics: Rethinking Europe’s Worksites of Democracy.” In Border Lampedusa: Subjectivity, Visibility and Memory in Stories of Sea and Land, edited by Gabrielle Proglio and Laura Odasso, 87–101. London: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59330-2_6.

Osman Balkan is Associate Director of the Huntsman Program in International Studies & Business at the University of Pennsylvania and author of Dying Abroad: The Political Afterlives of Migration in Europe (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

© 2024 Osman Balkan

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.